Digitalisation: Google

I corrected and adjusted several passages broken due to the digitalisation, de facto re-copying most of the document.

The articles I sometimes post have, in my opinion, great value. They portray topics and situations as seen from the perspective of “insiders” in the era they were written. They allow us enthusiasts to learn something new, and understand how technology, tactics and perceptions have changed throughout the years.

They deserve to be shared and preserved.

Every smart fighter pilot knows that being able to control a fight is essential to victory. Without a solid grasp of fundamentals, few fighter pilots will last long in the high-intensity environment of modern air combat. The ability to assess the tactical situation quickly and act is crucial.

The objective is to kill the bandit prior to the merge with all aspect ordnance or to arrive at the merge with a positional and/or energy advantage that facilitates a rapid kill.

Improvements in radars, radar warning receivers (RWR), airborne and ground-controlled intercept (GCI), and air-to-air training have enhanced the fighter aircrew’s ability to detect opponents beyond visual range (BVR). In addition, the improved performance of new generation fighters allows relatively late visual pickups to be turned into high aspect passes.

The result is fewer engagements begun with one player having an overwhelming offensive advantage. Consequently, the skill and proficiency required to turn a high-aspect entry into an advantage – and obtain a quick kill – are essential to success in today’s tactical arena.

Basically, fighting tactics can be broken into four phases: detection, interception, engagement, and separation.

Detection

Before the bandit can be engaged and killed, he must first be detected. Detection ranges can vary from close visual pickups to radar contacts in excess of 40 miles.

The objective of the detection phase is to analyze the bandit’s flight parameters and maneuvers so that an intelligent engagement decision can be made. The quality of that analysis is time and distance dependent. A long-range radar contact will provide altitude, true airspeed, mach, heading, aspect angle, range – and most important – the time to interpret this information.

Short range contacts do not provide much time to assess the situation; however, line-of-sight (LOS) rate, closure, nose position, and flight maneuvers can provide an estimate of the bandit’s energy level and awareness of our presence. Other visual cues such as engine smoke, afterburner plumes, and wing sweep angles can also update this analysis. A visual identification (VID) of the bandit aircraft will provide his performance, avionics, and weapons capabilities.

Observing changes in an adversary’s parameters and maneuvers may provide answers to some or all of four important questions:

- Is the bandit aware of our presence?

- What are the bandit’s intentions?

- What are our relative energy states?

- What is the bandit’s level of competence?

By answering these questions, an estimate can be made as to how long it will take to kill the bandit. If more time is required to achieve a kill than is available in the tactical situation, then the engagement should be avoided. Many tactical situations may not allow time to kill the opponent, regardless of how little time is required to do so. In the multi-bogie arena, it is neither necessary, nor healthy, to engage every bandit detected. Very often, discretion is the greater part of valor.

Interception

Following detection is the interception phase of the engagement. There are four objectives to achieve during the intercept:

- Sort and target the bandit formation and achieve a final radar lock-on, if desired.

- Gain turning room on the enemy.

- Manage energy.

- Employ ordnance.

During a long range engagement, the intercept objectives can be accomplished in a timely manner. On the other hand, a short range engagement will require that all the objectives be accomplished simultaneously. There may only be time to turn, boresight, and shoot an AIM-9L/M. In some instances, there may not be time for that! Again, time and distance are critical. For the sake of the discussion, assume that sufficient time and distance are available to accomplish the desired objectives.

Prior to taking a final radar lock-on and employing ordnance, an attempt should be made to sort the enemy formation and intentions. Sorting is important to build situational awareness (SA) of bandit tactics and intentions prior to the merge, and to target the different bandits. Do not, however, lose sight of the primary objective, which is to employ ordnance and eliminate the opponent in minimum time. A killl with a BVR radar missile is outstanding! A backup AIM-9L/M can also finish off the bandit with a front quarter kill. Unfortunately, no weapon, or combination of weapons, has a 100 percent probability of kill (PK). The enemy – being notoriously bad sports – uses deception, electronic countermeasures (ECM), and infrared countermeasures (IRCM) to degrade and defeat our weapons and tactics. In addition, late detection, degraded fire control systems, VID requirements, and large numbers of adversaries can all contribute to poor SA and, possibly, allow one or more of the bandits to reach the merge alive. Therefore, the intercept must be planned for that contingency.

During the intercept, attempt to gain turning room horizontally and vertically. Environmental conditions, such as sun position, sky conditions, cloud, haze, contrails, and background, will indicate where the turning room will provide the most difficult visual problem for the bandit. Large altitude deltas, in conjunction with chaff and ECM, can degrade or deny the enemy’s radar acquisition. Altitude separation below the bandit will provide the multiple benefits of turning room and clutter-free shots, while giving the enemy both infrared (IR) and radar clutter problems.

Turning room is available in all planes, and any turning room – even a few hundred feet – represents an advantage if properly used. There are, however, some cautions to keep in mind. Once turning room is established, it is there for both players. An aware, competent, opponent will take advantage of turning room; or, at the very least, deny its use to the other pilot. If the bandit is denying turning room and actively attempting to set up a lead turn, stop trying to gain turning room on the bandit. Once the adversary has established pure pursuit, turning room is diminishing. Further attempts to gain turning room are counter productive and only provide an angular advantage to the enemy. Thus, maneuvering room can only be generated against unaware, unskilled, or incompetent bandits.

Proper energy management is a continuous objective of the intercept phase and is essential to success. One of the best intentioned, but most misunderstood, phrases in air combat vernacular is “SPEED IS LIFE!” Entering an engagement at high speed provides the opportunity to:

- Disengage and separate.

- Trade airspeed for altitude.

- Fight a high energy fight.

Too much airspeed at the wrong time, however, can be just as deadly as too little. Speed is not life – PROPER ENERGY MANAGEMENT IS.

Turn rate and radius are a function of true airspeed and “G” – nothing else. For a given “G,” the turn rate decreases and the turn radius increases as airspeed is increased. Every fighter has its own instantaneous and sustained corner velocity, as well as its best acceleration “G” and energy bleed rate. Whatever the airplane, the pilot must have perfected the advanced handling and BFM skills necessary to attain the maximum performance of the fighter. Aggressiveness is essential. When it is time to turn the airplane and establish nose position, then TURN! When it is time to unload and accelerate, DO IT! Don’t accept halfway measures.

Common errors in BFM include: failing to slow down when it is time to generate a high turn rate with a small turn radius; and, failing to unload to the proper acceleration “G” when attempting to regain energy. All too often, pilots are observed flying 500 knots or more, pulling 7 “Gs,” and wondering why they are being arced for guns. Or, conversely, after sustaining high “G,” the same pilot unloads from 7 to 4 “Gs” and wonders why he cannot accelerate away from the bandit.

BFM is obviously flown by using outside references and not by looking inside at the airspeed indicator and “G” meter. The pilot must be able to “feel” the airplane. Success at BFM depends on maintaining the balance between energy management and nose position. It is the ability to properly decide when to trade one for the other that separates the winners from the losers. Remember the intercept phase objectives:

- Time permitting, radar sort, target, and lock-on to the bandit.

- Gain turning room so that an advantageous entry is attained at the merge.

- Manage energy so that a full range of options is available at the merge.

- Take all shot opportunities. Never fly through weapons parameters. The most successful engagement occurs when the enemy is destroyed four miles away and a turning fight never develops.

Engagement

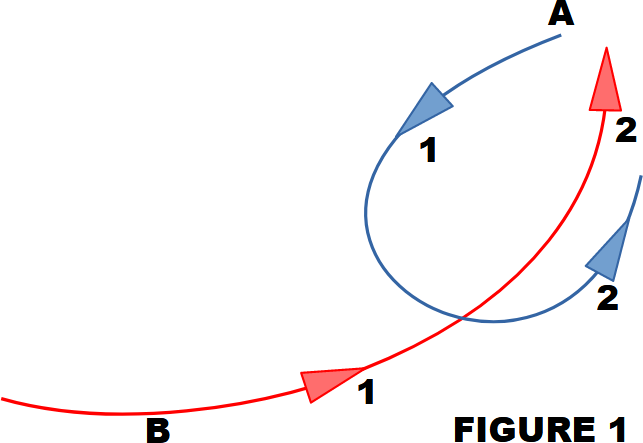

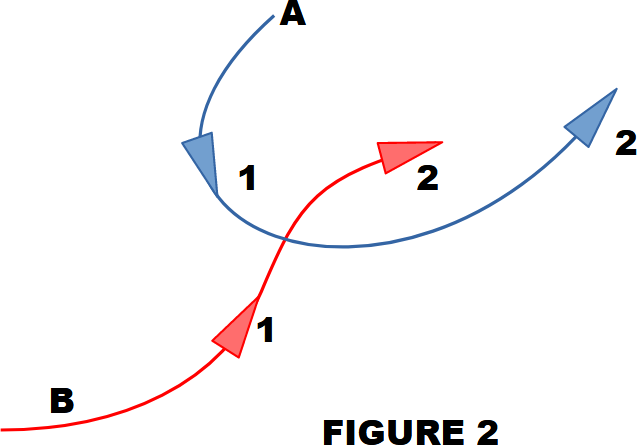

Unfortunately, despite valiant efforts, bandits sometimes survive to reach the merge. This situation demands proficient BFM. If the intercept has provided turning room, and engagement with the bandit is desired, a properly executed lead turn can rapidly provide an offensive advantage. Before continuing this discussion, however, a lead turn needs to be defined. A lead turn is one that is started in front of the enemy’s 3-9 line with an angulate advantage – not to turn in front of him (see Figure 1). In the F-15, a good rule of thumb is to start the lead turn when the bandit is on the canopy bow. The more turning room that has been established, the further out the lead turn can be started. Generally speaking, do not show the aircraft belly to the adversary. Doing so is a good way of winding up in front of the bandit. An opponent of similar, or superior, turn performance is capable of turning inside the attacker’s turning circle and it then becomes questionable as to who is lead turning room whom (see Figure 2). The exception to the rule occurs where the bandit is incapable of generating a good turn rate due to excessive speed or vastly inferior turn capability. In the case of a high speed opponent, it may be necessary to fly lead pursuit (showing him the belly) in order to get an opening VC shot from the rear quadrant.

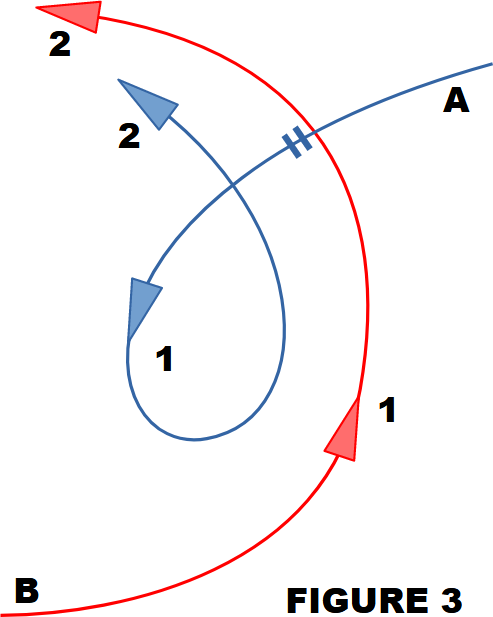

While turning room is available in all planes, the vertical lead turn can provide a rapid advantage provided the bandit allows the opponent to gain vertical maneuvering room and does not counter the lead turn at the merge. Turning in the vertical against a bandit who fails to recognize the developing advantage and defends only in the horizontal, or nearly horizontal plane, provides the opportunity to turn inside an adversary’s circle and behind his 3-9 line. Assuming the bandit does not counter the vertical lead turn early, it will be relatively easy to pirouette and roll into an offensive position. Proper power and airspeed management are essential to the success of this maneuver. Too little airspeed and power going up will result in insufficient energy to maintain the

advantage. Too much airspeed going down will reduce the turn rate and increase the turn radius to a point that may negate any initial advantage of vertical turning room (see Figure 3). Often, two opponents will approach the merge with each attempting to lead turn the other one in the horizontal and one in the vertical. Provided that the aircraft are of equal performance and similar energy states, the attacker that uses the vertical should have an initial nose position advantage. This is due to the radial G that is available going over the top. If unrecognized by the bandit maneuvering in the horizontal, the nose position advantage can intimidate and cause errors leading to a sustained offensive position by the attacker. When engaging bandits with a

lower thrust-to-weight ratio, this option is especially effective. Accordingly, when facing equal or superior performing adversaries, do not allow them to gain and use vertical turning room to their advantage.

As noted in the discussion of turning room, an aware, competent enemy can deny the lead turn if he has sufficient energy to generate the required turn rate. In the final analysis, a lead turn can only work on someone who fails to counter the maneuver. Remember, if the opponent has acquired vertical turning room and is attempting a vertical lead turn, counter and deny his attempt.

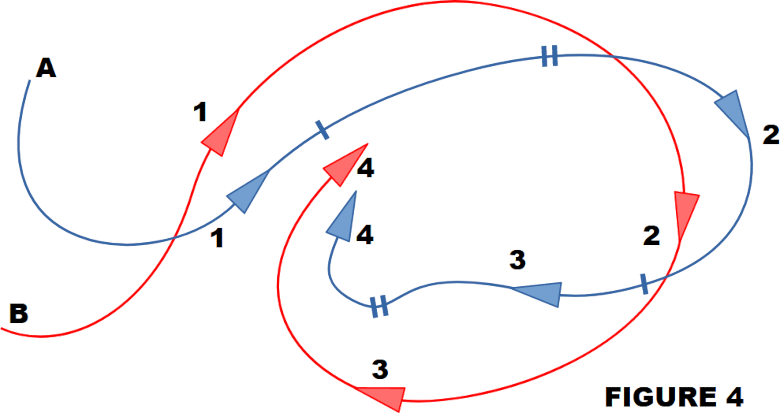

Rarely does a single turn result in an immediate kill. Patience is a must. Several successive lead turns may be required to achieve the position necessary to eliminate the bandit especially when employing stern-only ordnance. This is where the balance between energy and nose position is most graphically illustrated. An initial lead turn may give a positional advantage to the attacker; however, energy is dissipated during the turn (see Figure 4). In order to continue to pressure the bandit, the attacker may have to relinquish some nose position in order to regain lost energy. At the same time, the attacker plans his next lead turn. Each lead turn, in sequence, enhances positional advantage until weapons parameters can be achieved.

The greater the disparity in aircraft performance and ordnance, the quicker the kill. However, when facing a proficient pilot in an equal airplane, the outcome will depend on pilot skill and will usually take much longer to determine. If the bandit denies turning room and the lead turn, a high aspect pass will result. The choice then becomes a one circle fight, a two circle fight, or a separation. Each option presents advantages, disadvantages, and opportunities in various situations.

One Circle

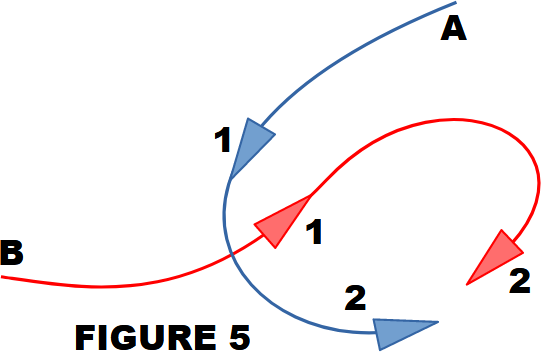

How does a one circle fight occur? As two fighters merge on a left to left pass, both aircraft turn into each other. One fighter then reserves his turn and generates a single circle fight (see Figure 5). The result is similar to an offensive fighter committing a flight path overshoot after which the defender reverses. The magnitude of the overshoot is such that the reversal initially keeps the opponent neutral.

The objective of a one circle fight is to gain an offensive position behind the bandit’s 3-9 line in minimum time. To accomplish this, it is preferable to fight against an enemy who has inferior turn performance and a lower thrust-to-weight ratio. For example, an F-15 turning against a hardwing F-4 would like to force a one circle fight. The F-15’s superior turn performance will allow the pilot to rapidly establish a position behind the F-4’s 3-9 line. By so doing, the Eagle driver can shoot the Phantom, while denying the Phantom a shot opportunity.

What are the advantages of a one circle fight? Although the turn initially maneuvers the bandit across the six o’clock area, the opponent is kept relatively close during subsequent maneuvering. Small adversaries are difficult to see when they get more than a couple of miles away. Lose sight, lose fight!

When maneuvering against bandits with inferior turn performance and all aspect ordnance, the one circle fight denies the use of the ordnance and allows the better turning aircraft to achieve a quick kill with relatively little energy loss. Also, because the one circle fight is usually small, it is difficult for additional bandits to enter the engagement.

What, then, are the disadvantages of the one circle fight? The bottom line is this: if maneuvering against a competent enemy with a better turning airplane, it will be difficult to survive the encounter! Against equal or similar performing aircraft, the fight can take a long time to win; all the while, the fight anchors in one spot making it easy for new opponents to find the fight. In addition, the fight tends to get slow, ending in some type of a vertical rolling or flat scissors.

Surviving the one circle fight results in a low energy state, poor SA, and an easy prey for additional bandits hawking the fight. Finally, mutual support may be degraded because it is difficult for a wingman to enter a tight, slow fight, or to effect an element separation.

Two Circle

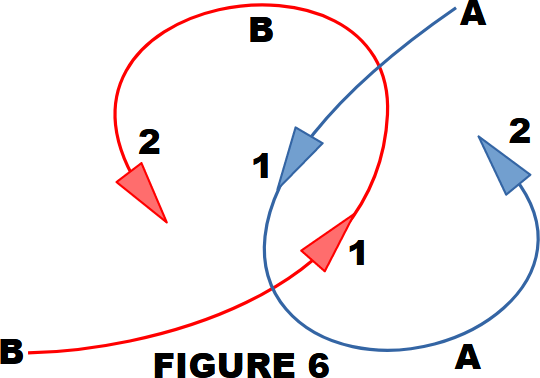

How, then, does a two circle fight occur? As two fighters merge on the same left to left pass, both aircraft turn into each other. This time, however, no one reverses. The turns continue and establish what resembles a figure-eight pattern (see Figure 6). If both aircraft were to maintain constant airspeed and “G,” the figure-eight pattern would continue indefinitely.

The objectives of the two circle fight are to kill the bandit by employing all aspect ordnance or to lead turn him at the next merge in order to maneuver behind his 3-9 line. The two circle fight presents excellent opportunities against bandits that do not have an all aspect capability. For example: if an F-5 commits against an F-15 and the Eagle can force a two circle fight, the superior turn capability of the F-15 enables the pilot to bring his nose to bear on the F-5 and, thus, employ an AIM-7 or AIM-9L/M. Once again, the Eagle driver is in a position to shoot all aspect ordnance

at a target that cannot shoot back. If the front quarter shot is unavailable or unsuccessful, the opportunity remains to lead turn the adversary at the next merge; or, to disengage and separate.

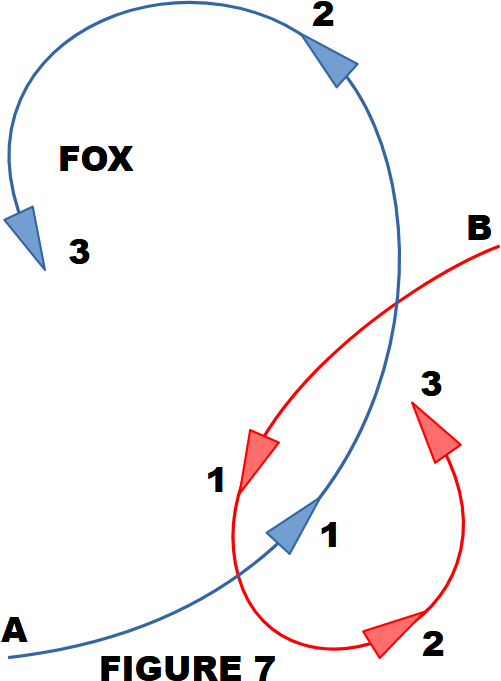

Tactically, it is not sound to engage a bandit with superior turn performance, avionics, and weapons in any type of a turning fight. However, the two circle fight does provide the option of engaging a superior turning aircraft successfully for a limited time period by maintaining a high energy fight. This negates the bandit’s better turn capability. To be successful, it is essential to deny the lead turn at each merge, keep the airspeed high, and employ front quarter ordnance (see Figure 7).

What are the advantages of the two circle fight? Generally, the fight is kept larger and the airspeed is kept higher. Avionics and weapons that provide a rapid off-boresight launch capability offer a tremendous advantage in this situation. Initially, the fight is not slow and small; thus, SA and energy are easier to maintain. In addition, the wingman should be able to support the fight or effect an element separation. Finally, when fighting a high energy, two circle fight, the option to separate is more readily available.

A disadvantage of the two circle fight is the difficulty in keeping sight of small targets. This can be a significant factor since the turn at the merge maneuvers the bandit to six o’clock. Another disadvantage occurs when engaging a bandit with all aspect ordnance. Having survived the merge, it may not be prudent to allow the bandit room to maneuver to front aspect parameters – especially if you are flying a superior performing aircraft that could deny any shots by maneuvering behind the adversary’s 3-9 line.

The choice between a one circle or a two circle fight depends upon the type of fight that the participants desire. The problem occurs when each participant opts for a different fight. A feint at the merge that forces the bandit into his initial turn may then allow a reversal and the establishment of a one circle fight. The main point of the discussion is that the decision should be based on the type of adversary and the tactical situation. Whether to take the fight up or down will be a function of relative energy states and aircraft performance capabilities. When energy and aircraft performance are superior to that of the adversary, taking the fight up can provide a rapid advantage. If at an energy deficit, taking the fight down can generate energy and offset the enemy’s current advantage. The keys to success are in properly assessing relative energy states and in knowing where the energy maneuverability (EM) advantages/disadvantages are against various bandit types. Select the fight that presents the best opportunity for a quick kill and then force the desired fight. Do not let the opponent dictate the terms of the engagement!

Separation

How is a successful separation accomplished? First, the need to disengage and separate must be anticipated. High airspeed and denial of the enemy’s turning room are important factors. Separating from the initial merge is not a particularly difficult task. A full afterburner acceleration, while denying a bandit turning room, should allow supersonic airspeed at the merge with a large heading crossing angle (HCA). The problem becomes more difficult, however, when the fight has progressed through several turns and energy states are depleted. This situation requires anticipation and planning in order to accomplish a successful separation.

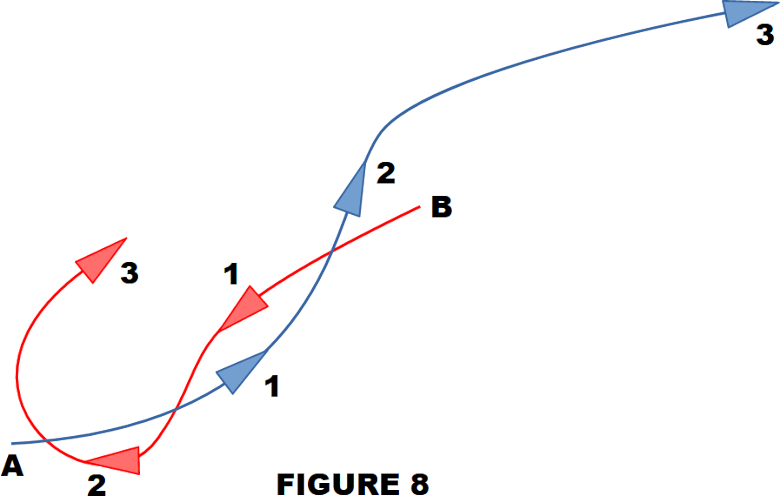

Once the decision to separate has been made, it becomes necessary to accelerate and deny the adversary turning room. If turned into by the bandit at the merge, check into him as if to initiate a two circle fight. This should develop a HCA close to 180°. If the enemy reverses and attempts to force a one circle fight, reverse the check turn to maintain the maximum HCA (see Figure 8). The check turn should not be continued allowing the bandit to arc. The objective is to achieve a full 180° aspect with the foe. It is essential to maintain visual contact with the adversary and accelerate away from him. If the bandit wants to force the fight, his hard turn at the merge will generate more turn rate and he will eventually bring his nose to bear; but, it will cost him energy. By checking into the bandit at the merge, he is forced to turn more than 180°; thus, providing the time to accelerate and separate. Additionally, any lead turn is denied, maximum HCA is created, and possibly, the bandit may lose visual contact. Remember, if energy becomes depleted during a turning fight, it may be impossible to separate. The basic concepts of pressure and control are extremely important when engaging an adversary from a high aspect. The primary objective of the engagement must always be kept in the forefront: KILL THE BANDIT IN MINIMUM TIME AND LEAVE THE ARENA! The purpose of BFM is to achieve weapons parameters as effectively and efficiently as possible. Pressure the bandit with the continuous threat of weapons employment. Control the fight by taking the initiative and make the opponent react. Force the type of fight geometry desired; be it one circle, or two circle. FIGHT ON YOUR TERMS, NOT THE BANDIT’S! Finally, if the conditions are not favorable, disengage. A prolonged turning fight in the multi-bogie arena is an invitation to disaster.

There it is the collective ideas of two Eagle drivers on how to gain and maintain the advantage. Remember, control the battle and fight aggressively. Good luck, and good hunting!