This article approaches low-level planning purposely without diving into the rabbit hole. It should suit players who prefer a relatively quick and dirty approach over a more methodical one. Later chapters will discuss the particulars of these techniques in greater detail.

Plan Phases

Flying at low levels, below 500ft and down to double-digit altitudes, is only a portion of the complete mission. At least three sections can be identified:

- Departure until low-level;

- Low-level portion;

- Post low-level and recovery.

Fighters can operate at higher altitudes before entering and after leaving the area where the target is located to save fuel, simplify navigation, and so on. Therefore, a flight plan may see the first portion flown at high altitude, then low level, and eventually high altitude again. The resulting profile, “High-Low-High” or “HLH”, and the ordnance carried affect fuel consumption and timings differently from a “Low-Low-Low” or “LLL” profile. Given the simplified nature of this article, these considerations are left out for a later time, and only the central low-level part is discussed.

Low-Level: Considerations

The starting point of the low-level portion is generally called the “Entry” or “Penetration” point. This is where the chronometer or clock starts.

Once the target and the penetration point are identified on the map, the focus shifts to “how to get there in one piece”. A long list of factors should be taken into account. Let’s see some basic elements:

- Direct vs indirect route to the target. A direct approach reduces time and fuel consumption, but may be unsafe to follow.

- Terrain features and hazards, such as obstacles, should be located and identified.

- Landmarks and references ease navigation, but cities and towns should be avoided to minimise detection. At least in a game, we are not too worried about disturbing non-simulated civilians…

- If known, variables such as enemy location, air defences, and CAP tracks should be considered. Friendly assets and missions should be likewise noted. Since fuel consumption is higher down in the weeds, available tankers are especially important.

It is worth spending a few more words discussing some points from the abovementioned list.

Avionics

Depending on the type and era of the aircraft in use, a series of helpful tools may or may not be available to the crew. For instance, the TFR, or Terrain-Following Radar. Away from dedicated instruments, most aeroplanes carry at least a radar altimeter, or “RADALT”.

The barometric altimeter may sound like a valid alternative, but such a device is safe to use only above the maximum elevation of the terrain plus a safety offset. Moreover, the crew must pay extreme attention to the Q-setting. Therefore, failing or missing other devices, the radar altimeter is the primary tool to monitor and maintain separation from the terrain. A good set of Mk I eyeballs helps as well!

Routing and Hazards

A route that maximises terrain masking may sound ideal, but with uneven terrain comes the serious danger of impacting the ground. For this purpose, each leg should record a minimum safe altitude, particularly useful during night or poor weather operations.

Man-made objects, such as power lines, antennas, isolated and tall buildings, may constitute a hazard to low-level flight. Extra attention should be paid to such objects, especially in suboptimal visibility. These features, however, have a very useful characteristic: they develop vertically.

Landmarks, Checkpoints and References

Two significant problems of flying at low altitude and high speed are the perspective and the short time to analyse information. Since the point of view is quite close to the ground, features with considerable height are much simpler to spot than features that extend horizontally. For example, assuming you do not live in a particularly elevated area, when you look outside, you may be able to spot a bell tower, a powerline mast, or a skyscraper better than a junction or a motorway.

Flying at a high altitude instead flips the perspective, and landmarks that develop horizontally are simpler to identify than vertical ones.

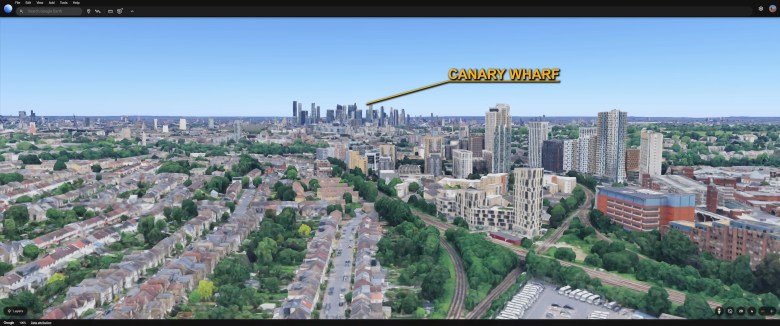

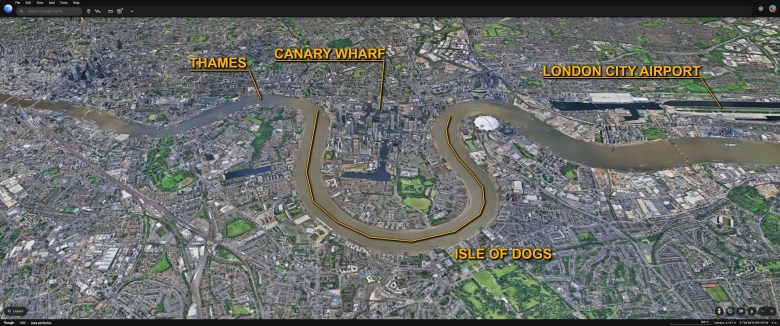

This issue is simply explained with the following images.

This is the view of Canary Wharf in London from the South. Despite the River Thames embracing the whole Isle of Dogs, only the financial district’s skyscrapers are easily recognisable.

If we move the perspective higher, then London City Airport and the Thames become unmistakable landmarks.

When planning a low-level sortie, appropriately selecting visual references and landmarks becomes fundamental. This is fairly easy on a purposely designed map, but much harder in DCS. For this reason, I am making my own maps to be used with the tool I am developing.

Good checkpoints should have many positive aspects. For example, particularly useful are funnelling features, such as a valley, a wide river, or a motorway that runs along part of a leg, serving as a contiguous and prolonged positional reference.

Another important characteristic is the uncommonness. A small non-seasonal lake in an otherwise dry area is quite unique. A small lake in the Finnish Lakeland, not as much. Similarly, a skyscraper in a small town may be the tallest and most recognisable building. The same skyscraper in a bigger city may just be one of the many.

A simple and useful exercise is to describe the flight plan in words as if it were being told to someone asking directions. At the same time, the crew should try to imagine how the features on the map will look in-game, either visually or on the air-to-ground radar display.

Back to planning, checkpoints and references should be identified along the planned route and located within a couple of minutes of each other, with a maximum interval of 5 minutes. DCS-wise, shorter intervals are advisable to make navigation simpler. At the end of the day, we do not spend many hours daily training and practising as real crews do.

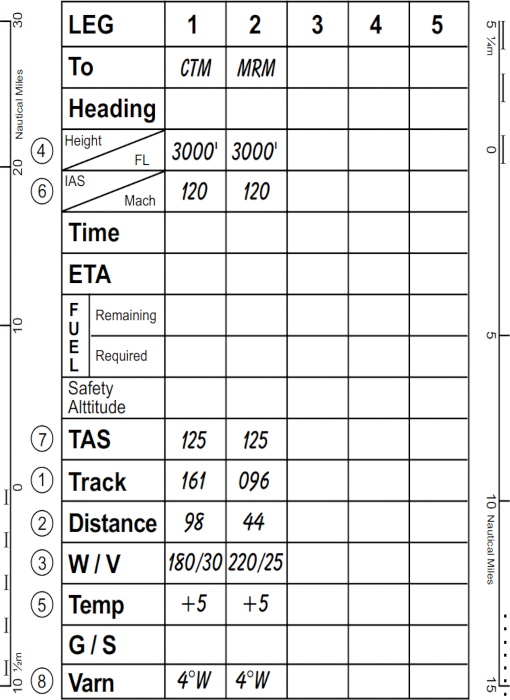

Nav Log

Once the route has been decided, it is time to review the plan and, if happy about it, collect data about course, true air speed, and distances. These values are noted in a Navigation Log or the Nav Tools I shared recently. Manually filling out a Navigation Log and calculating wind effect, magnetic variation, approximate IAS, and other parameters is a time-consuming endeavour, so I suggested an automated solution.

When everything is computed, the values of TAS, heading, time, altitude and so on can be noted, or ad hoc kneeboard pages can be prepared. At this point, we should have all the basic elements to fly the mission.

Here is a quick tip about TAS: choosing a value multiple of 60 allows for instantaneously computing distances. For instance, when flying at 420 kts, 7 nm are covered every minute, since 420 divided by 60 is seven. Similarly, 540 kts means covering 9 nm per minute since 540 is divided by 60. To speed things up, remember basic maths: the zeros can be elided, and the resulting operation is a de facto times table from elementary school.

Corollary to what was just said, we find that 30 kts allow for half-miles to be immediately understood. For example, 450 kts equals 7.5 nm per minute, since 450 is 420 + 30.

Conclusions

What is discussed in this video should be sufficient for a first low-level plan and execution. These are the factors worth remembering:

- The radar altimeter is a reliable and ubiquitous device to measure the aircraft’s altitude.

- Routing should take into account threats and terrain whilst optimising short length. Intuitively, the sooner the crew leaves the hostile area, the sooner it should be safe.

- Scanning outside should be a high priority during the flight, not only to check landmarks and references but also to spot threats and obstacles and monitor the terrain.

- When selecting checkpoints, remember that game and map have almost orthogonal perspectives.

- Desirable characteristics of checkpoints are: vertical development, uniqueness and persistency. The last point rarely applies to DCS, but texture variations between summer and winter maps may make some landmarks less recognisable.

Going forward, things will get a bit more complicated, with more in-depth discussions about minutiae and other details.