Part III of the Low Level series covered how the crew can approximate the effects of wind on the spot using the “clock method”. This article continues on the same path, discussing how timing corrections can be executed.

Types of error

A combination of dead reckoning and pilotage monitors the low-level portion of a mission. The chronometer beats the time of each leg, whilst checkpoints and landmarks help the crew verify their plan. Nevertheless, unexpected situations, errors in the planning, or other factors may demand a timeline adjustment.

Errors generally fall into two categories: “cumulative” and “one-off” errors.

- Cumulative errors tend to increase as the flight progresses. For example, let’s take a checkpoint located at ⅓ of the leg and, once the aircraft reaches it, the crew notice that they are 30s late, but they were spot on at the beginning. If the situation is not addressed, the new error introduced by the new condition will lead to a 60s delay at ⅔ of the leg and circa 90s at the end. In other words, if the situation does not change, not only is the error not addressed, but it increases minute after minute.

- “One-off” or “once-only” errors are caused by a general disruption of the plan, not a constant condition. For example, if the crew reaches the beginning of the leg 1 minute later than expected, and it is not a new state, such an error should be constant along the leg and, if not addressed, reverberate on the next leg.

Understanding the type of error the crew is running into and addressing it is important to respect the planned schedule. The following are methods applicable to do precisely that.

Speed Management

There are various techniques to regain the lost time. The simplest is to change the fighter’s speed.

For example, given a certain distance remaining in the leg, for example, 14 nm, we have:

- At 360 kts, 6 nm are covered every minute, 2.3 minutes are required, therefore 2m 20s;

- At 420 kts, 7 nm per minute are flown. Therefore, it takes 2 minutes to cover 14 nm;

- At 480 kts, every minute 8 nm are covered, leading to 1.75 minutes or 1 minute 45s.

- Flying at 540 kts, so 9 nm per minute, the required time drops to circa 1.5 minutes, ergo 1m 30s.

Therefore, if 420 kts were the speed planned for the leg, by accelerating to 540 kts, the crew can recuperate 30s.

The elephant in the room is that jet engines operating at low level tend to consume much more fuel the higher the required speed.

Dogleg

A solution suggested by Gaby, an Armée de l’Air Alpha Jet and Mirage pilot, is the so-called “Dogleg”. This peculiarly named technique uses a leg whose raison d’être is to be trimmed or skipped entirely to catch up if the crew falls behind schedule.

Apparently, the name refers to the anatomy of dogs’ legs. Since we are here, “leg” is borrowed from sailing and/or railway lexicon. The more you know…

Gaby’s articles and maps can be found on his Patreon page here.

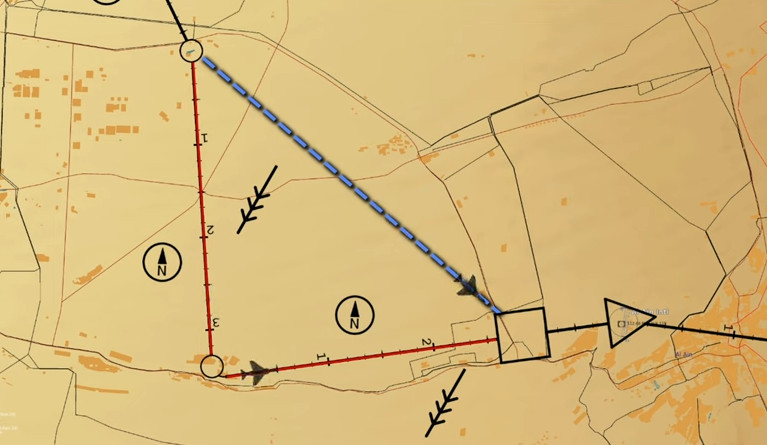

Using the familiar Persian Gulf map and the flight plan shared in earlier tests, we can ignore the waypoints/IP/TGT and imagine that the highlighted legs serve the described purpose. If necessary, they can be skipped, and the aircraft can proceed directly from WP1 to WP3.

Introducing a dogleg is facultative, but it is good practice, especially as the mission grows in complexity.

For example, a straight leg can be split into two legs following different headings. De facto, this creates a triangle formed by the original leg, the hypotenuse, and the newly created pair as the two sides. Intuitively, since the hypotenuse is always shorter than the sum of the two sides, the crew can follow such a leg to compensate for the lost time.

Organisational shift

Vulture, ex F-4E WSO, raised important points that, to be fully appreciated in the context of the game, require a higher perspective. Although these considerations are more relevant in a broader debate about package planning, coordination and execution, they are worth mentioning for completeness. Later, dedicated discussions will delve deeper into these concepts.

The brevity “Rolex” is designed to manage the mission schedule.

ROLEX [± time]: [A/A] [A/S] Timeline adjustment in minutes for entire mission; always referenced from original preplanned mission execution time. “Plus” means later; “minus” means earlier.”

Delaying the mission execution is an action that should be carefully considered. For example, it must be called before the original push time, the package should still be in friendly territory, and before the last fuel top-up. Otherwise, fuel may become a limiting factor.

A “trombone” leg may also be planned. This construct is similar in purpose within this context but different from the previously discussed dogleg. The trombone is often used in civil aviation to manage and merge traffic. In military aviation, instead, it refers to a manoeuvre executed usually before starting the low-level segment. The name derives from the shape that paths often assume, which resembles, guess what, a trombone.

An important point raised by Vulture is the necessity of having a backup plan. Delays reverberate and affect every part of a mission, creating new issues in terms of schedule, organisation, cooperation, deconfliction, and fuel.

The nuances of this part of the discussion will become clearer once the package planning is discussed.

Before moving to the next topic, the always fantastic Vulture added a few more details about doglegs and trombone.

“A trombone is normally used before the low level, and is basically an orbit (or just an extra turn point beyond the start Low-Level point), positioned 90° to the route that you can cut short to turn back towards the start Low-Level point and hit it on time.

A dogleg is less acute, perhaps a 45° or 60° zigzag leg early in the route that is figured to allow saving a known amount of time if you skip the offset turnpoint and just go direct.”

The caveat is that different countries and organisations might use similar tools but in various ways. For example, the mentioned trombone is used differently in military and civilian contexts.

Cutting Corners

Lastly, I decided to have a go at maths and wondered whether the crew could simply “cut the corner” and turn towards the next leg before planned. The idea immediately raises a few red flags. Nevertheless, to entertain the argument, let’s see how effective this could be.

To make things simpler, let’s ignore the turn time. The result is quickly calculated using the Law of Cosines.

|

Example I

Heading from Leg I to Leg II: 140°

By turning 30s earlier, a flight planned for 60s would instead take 56 seconds — a non-exciting save of 4 seconds. If the aircraft turns 60s earlier, a flight that would require 2 minutes would instead require 112 seconds. |

|

Example II

Heading from Leg I to Leg II: 100°

Tighter turns lead to better results. Using the same numbers tested before: Turning 30s earlier means requiring 46 seconds rather than 60s. Turning 60s earlier allows for saving 28 seconds. |

|

Example III

Heading from Leg I to Leg II: 45°

This scenario is probably unrealistic or rare, as such a tight turn is hard to manage in the air. Let’s see what the potential gains are: Turning 30s earlier leads to a saving of 37 seconds out of 60. Turning 60s earlier allows for saving 74 seconds. |

Intuitively, the quantity of time saved depends on how tight the turn between the two legs is. The tighter it is, the greater the gain. Once again, we can involve maths to explain why.

Considering the triangle created by the two segments, the angle within them, and the opposite side as the “cut”, we find that if an acute-angled triangle is formed, the base is quite narrow compared to the other sides. Vice versa, if an obtuse-angled triangle is formed, the base is wider, making the cut less convenient time-wise.

Fun fact: since the triangle created in this scenario is isosceles, figuring out both how much to turn to execute the cut and how much to turn to return on track is intuitive.

Track_return = 180 – Turn (complementary angles).

As mentioned, in real life, cutting a piece of the flight plan is probably not an acceptable solution for many reasons, spanning from coordination to deconfliction, and hostile forces. However, DCS is a game, so it’s fun and interesting to look at apocryphal solutions.