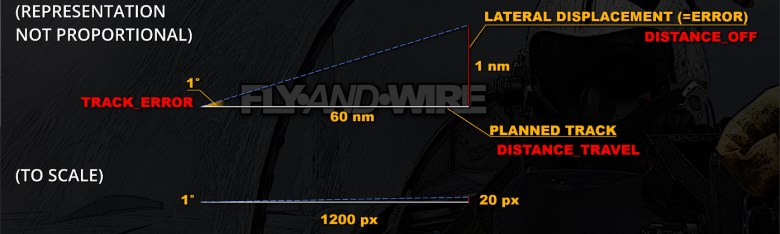

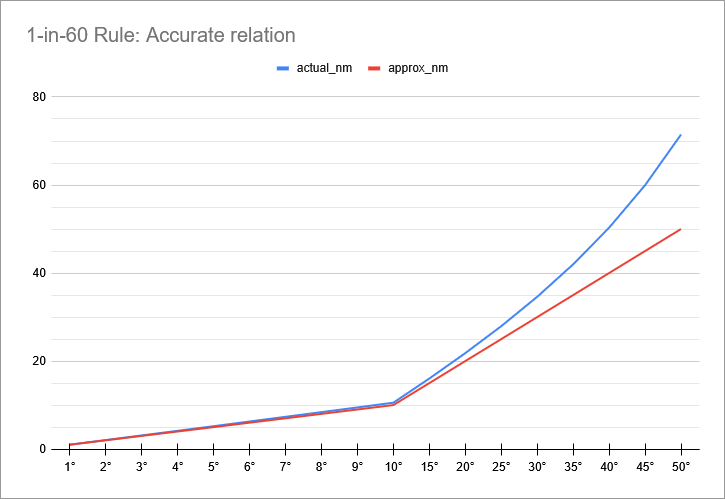

A handy trigonometrical relation describes that, for each degree off heading, the erroneous lateral displacement is 1 nm over a distance of 60 nm. Ergo, 1° approximates to 1 nm after 60 nm. 2° is circa 2 nautical miles after the same distance, and so on.

Although this relation applies only when the angle off is relatively narrow, circa less than 30°, it works well in the context of understanding and addressing navigation heading issues.

The mathematical formula behind the one-in-60 rule may sound familiar, as it is the same one used to determine the antenna elevation angle and related parameters on FlyAndWire a few years ago.

In the simplest case, where the drift is 1°, the lateral displacement is 1.05 nm, which is definitely close enough for the purpose of this method.

Using the One-in-60 rule

Using the rule requires the crew to act on two points:

- In primis, determine “how off” the aircraft is. Such a value is called “track error”;

- Then, address the issue by determining how many degrees the aeroplane should turn. This value is called “track correction”.

The crew can use any planned checkpoint or reference to determine the track error. The idea is to assess the distance between the aircraft’s current position and the reference location, along with the direction of such an error.

The track error is determined using this formula: distance_off / distance_travelled * 60. The formula can be rearranged to determine each variable.

track_error = distance_off / distance_travel * 60

distance_travel = distance_off / track_error * 60

distance_off = track_error / 60 * distance_travel

If the distance travelled is rounded to the nearest ten, the formula is simpler as 60, and the denominator, can be divided by 10.

The next step depends on the nature of the error the crew is facing.

“One-Off” Heading Errors

The discussion about Time Management, topic of Part IV of this study, briefly mentioned the two common types of errors crews can encounter: “one-off” or “once-only” errors, and “cumulative” errors. As highlighted by the Royal Institute of Navigation, each type of error is tackled using a different approach.

The former is a type of error that, as the name suggests, occurs once. For example, timing or fix-related issues can cause the aeroplane to go off track. Whatever the cause, the fighter now has a lateral displacement from the planned track, which must be addressed. The One-in-60 rule can help the crew identify how many degrees the fighter is off track and compensate. It is worth noting that the greater the required correction, the more the crew should be aware of the effect on time.

Example I

distance_travel = 3 * 60 / 30 = 6 nm

Ergo, the distance to cover before returning to the correct track is 6 nm. The airspeed can then be computed. For instance, at a speed of 480 kts, 8 nm are covered per minute. Therefore, ¾ of a minute is sufficient to return to the track.

Example II

Using the parameters from the previous example, where the lateral displacement was 3 nm and the distance to the end of the leg was 40 nm, we find:

track_error = distance_off / distance_travel * 60 = 3 / 40 * 60 = 4.5°

By adjusting the heading towards the original track by 4.5°, the crew should reach the end of the track over the planned fix.

This solution applies only to the “one-off” errors. The solution to cumulative errors is more complex.

Cumulative Errors

Cumulative errors are addressed in multiple steps. In primis, the error is recognised and removed. Then, the crew corrects towards the planned track, and a third and last correction allows the aeroplane to maintain it. Let’s break these points down.

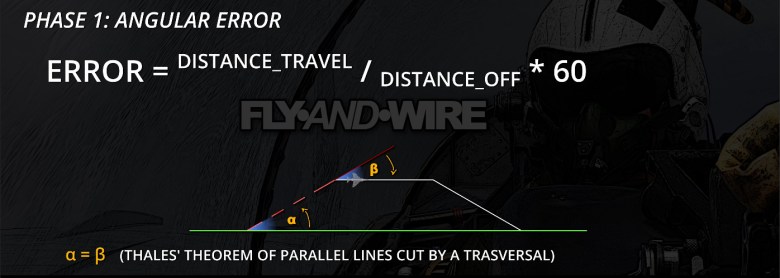

Phase 1 – Angular Error and Parallel Flying

Error = distance_travel / distance_off * 60

Once the error is known, the crew can turn towards the track for a number of degrees equal to the just calculated value, and it will now find itself following a parallel track.

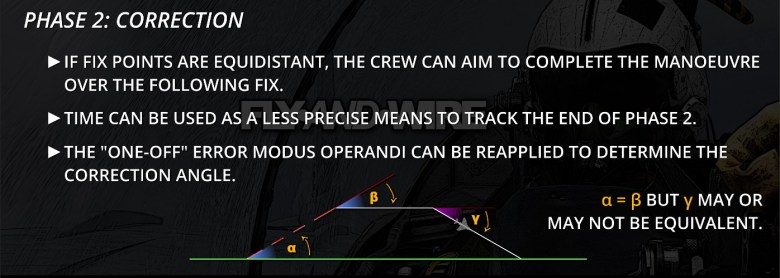

Phase 2 – Correction

- If the fix points are equidistant, the angle calculated in Phase 1 can be reapplied, and the crew should find itself on the track at the next fix’s location.

- Alternatively, if monitored, time can be used as a less precise metric to determine when the aircraft will reach the planned track.

- As described in the “once-only” error scenario, the crew can multiply by 60 and divide the distance from their position to the next fix or the end of the leg. The resulting angle allows them to return to the planned track.

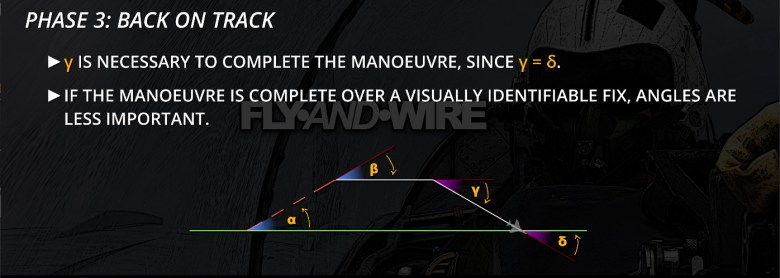

Phase 3 – Back on Track

The turn towards the original track, in fact, equals the previous angle. The reason is intuitive: the aeroplane was flying parallel to the track, then the crew introduced a heading variation to return to the original plan, and now such an angle must be removed.

Ab initio players may benefit by pre-planning the corrections. For example, by drawing a 5° error line on one side of the leg, acting as a reference to then interpolate other error angles. Similarly, drawing 5° reference lines towards fixes can help the crew to assess corrections.

A different perspective

As discussed, the One-in-60 rule is based on geometrical relations, the same used to determine the antenna elevation angle on FlyAndWire a few years ago. The same formulas can be applied to something very different, such as determining glideslopes and the rate of descent, and simplified through the usage of the One-in-60 rule. This topic goes well beyond the scope of this video and article, but the following is one of the many examples suitable to go deeper into it.

Avoiding Obstacles

The mechanics behind the error-correction methods described so far can be used to implement impromptu plan changes to avoid unexpected obstacles. This topic is more applicable to general aviation, but as always, DCS is a game, so it’s good to see different approaches to solving the issues we may encounter in our missions.

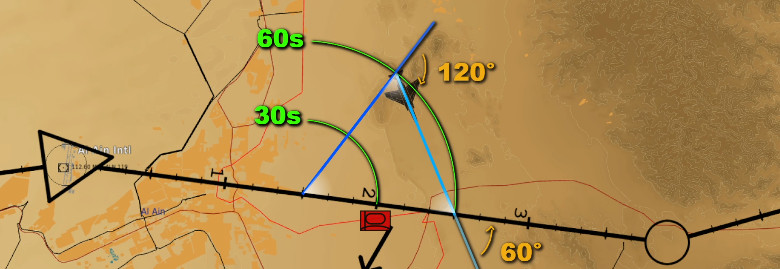

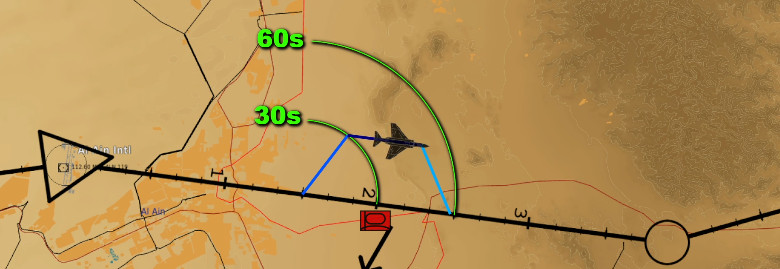

Obstacles can force the crew to consider a temporary diversion from the flight plan. A primary cause is the weather, but in DCS, meaner causes never lack. This technique involves a 60° turn away from the planned track for a specified duration. When the obstacle is cleared, the crew turns 120° into the track for the same amount of time. A final 60° turn in the opposite direction puts the aeroplane on the planned track.

A variation of the described techniques consists of reducing the second turn to 60° rather than 120°, placing the aeroplane on a parallel track. The direction is maintained as necessary before completing the manoeuvre as previously described, holding for the set amount of time and performing the last turn onto the planned track.

Time Management

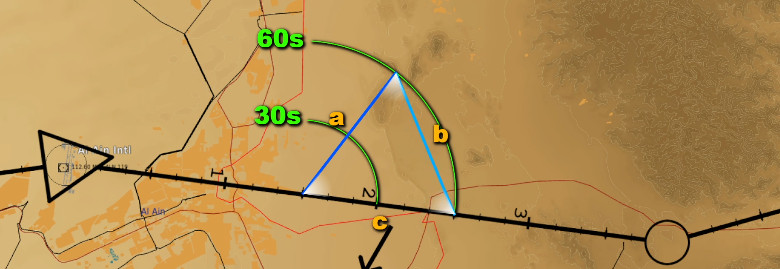

Curiously, this technique also serves as a simple time management tool. Although from a planning perspective, a “trombone” is more appropriate, the triangle created by the discussed technique allows for spending time if the fighter is early on its schedule.

If the 60° turns are respected, in fact, the created triangle is equilateral. Ergo, each side has the same length, and the total perimeter equals one side times 3. Assuming constant speed and negligible external factors such as wind, we intuitively find that the diversion takes exactly twice the time the original plan would have taken.

For example, at a speed of 420 kts, 7 nm are covered in a minute. If each side of the diversion is flown for one minute, then the manoeuvre is completed in 2 minutes, for a total of 14 nm. The original plan is the third side of the equilateral triangle, and is equivalent to any of the two sides of the diversion. Therefore, the manoeuvre has required twice the original distance and time of the original plan.

Spatial Separation

As a sidenote, and just because theorycrafting is a lot of fun, this manoeuvre can be used to introduce a spatial separation between two sections of the same flight. For example, if two sections are to attack the same target with a 60-second delay between them, elements 3 and 4 can turn 60°, hold for 60 seconds, and then return to the planned track. This would result in a 60s separation between the two.

This topic will be expanded later on in dedicated chapters of the Low Level study, but I wanted to mention it as a demonstration that, in a game, all sorts of tools can be employed to achieve an objective. Eventually, it is up to the players to stick to the SOP or leave the door open to more imaginative solutions.