Unplanned initially, I later expanded the discussion about the Sync-Z-Turn to show how its fundament concepts can be applied (sometimes forcibly and with several adjustments) to other modules:

- Sync-Z-Turn: Explanation (F-4E)

- Mirage F1;

- F-14 Tomcat;

- F-5E-3 Tiger II;

- MiG-21bis;

- MiG-29 Fulcrum.

What if I told you that a successful intercept does not require any information besides radar awareness? What if I told you that Aspect, Closure rate and so on can be completely unnecessary? And what if I told you that this technique is even easier than the various taught at the various OCU or RTU?

Interested? Then arm your AIM-9s because we are about to learn the magic of the “Sync-Z Turn”.

Video

In modern days, in the DCS universe, the idea of gathering the target’s information without a hard lock is common knowledge and a false privilege. Track-While-Scan, various forms of Range-While-Search and similar, usually provide tracks or range, altitude, aspect and so on. However, back in the 60s and early 70s, most radars could not do that. Systems such as the APQ-120 simply returned whatever happened to be in radar lobes, whether it be the coast, a mountain or a target. A hard lock was necessary to obtain the additional information mentioned above. However, depending on the technological level of the opposition, a hard lock could alert the target that something spooky was going on. Therefore, the ability to position the fighter and gain an advantage “quietly”, so to speak, is very valuable.

Introducing the Sync-Z-Turn, the first no-radar lockon intercept discussed so far, easily applicable to any fighter, Phantom II included.

Advantages

This technique enables a stern conversion behind the target in almost all situations, such as:

- Degraded GCI coverage, which is a non-factor in DCS at the moment, but hopefully, it will be in the future;

- The radar is used to determine the intercept’s parameters and, therefore, works both in day and nighttime and in adverse weather;

- As for all the intercepts that result in a conversion, it is handy for tanker rejoins and enables rear-quarter AIM-9 employment, a necessity when operating older Sidewinders.

Contrary to the overtake, checkpoints-based techniques, and similar procedures, the Sync-Z-Turn requires little information besides speed advantage.

The procedure as taught is already straightforward, but for the purpose of DCS and other games, it can be narrowed down further to two logical blocks:

- Situation assessment

The fighter assesses the cold side of the display and manoeuvres to place the bandit there. This generates lateral separation whilst decreasing the Aspect angle and increasing the Target aspect; - Azimuth synchronisation

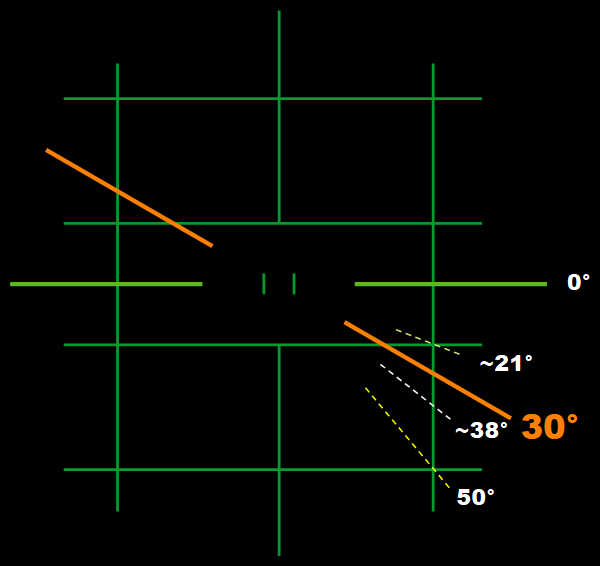

The fighter maintains the target at a predefined ATA. Once the bank angle necessary to maintain such an azimuth value reaches 30°, it turns to zero ATA or pure pursuit and rolls behind the target.

That’s it, pretty much.

This clever technique takes full advantage of the procedures and topics discussed so far. In fact, to explain why it works, we need to recall the relations between angles, aspect, drift, HCA and Cut, radar scope hot and cold sides, et cetera.

The video linked above, at 03:04, shows an in-game example. As you can observe there, all that’s needed is radar awareness, and even without prior information about the target, the manoeuvre works well.

Analysis

Let’s see how and why this technique works. This is important to respond to a bandit changing the geometry or gaining awareness.

Situation assessment

The procedure starts by assessing the target’s parameters. As usual, the better the Situational Awareness, the greater the advantage – or the smaller the disadvantage! For instance, the radar can be used to determine range and elevation, which immediately translate into the target’s altitude.

The determination of the “Cold” side of the display is necessary as the goal is creating a manoeuvring room to enable the stern conversion. For this purpose, the crew can zero the ATA by placing the target on the nose, thus allowing the drift to indicate the DoP and the display sides. In particular, the crew should pay attention to the drift ratio, which is greater the farther the contact is from the Collision Antenna Train Angle, CATA. Moreover, as long as the Cut is greater than zero, the target will always move away from the fighter, drifting away from the fighter and naturally increasing the Target Aspect or decreasing the Aspect Angle.

If in a zero-Cut or 180 HCA situation, then both sides of the scope are Cold, and the Phantom’s crew can choose their preferred side.

Range

Range deserves some consideration. If the range is greater than 30 nm, the fighter can fly a collision course to minimise the intercept duration. Alternatively, similarly to other intercept techniques already discussed, the crew can create room right away and then collision to capture the angles. However, given the lack of information, unless a radar lock is obtained, this option can drive the geometry off.

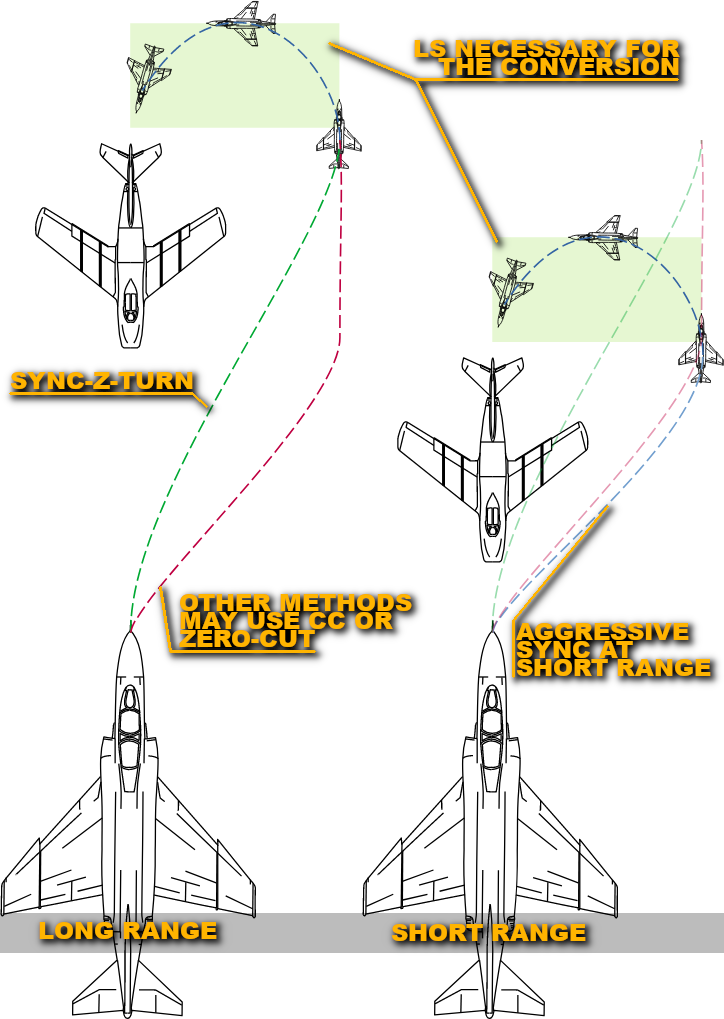

It is important to remember that the shorter the range, the greater the required offset, since there is less time, and, conversely, room for the fighter to increase the lateral separation. For Sync-Z-Turns at very short range, being aggressive with the Sync value can be beneficial and, worst case scenario, lead to a slight overshoot, which is not necessarily bad. Generally speaking, if the crew lacks the bandit’s information, the Sync should never be lower than 45°.

Next, the target is placed on the cold side of the display at a defined ATA value called “sync azimuth”. As discussed in the previous videos and articles, a contact not on a collision course will drift on the scope, and the drift ratio increases as a function of range and VC, and this is precisely what the Sync-Z-Turn technique uses. The fighter, in fact, should maintain the target at a constant azimuth, applying stick to the left or right as required. As the range decreases, the angle relations become more pronounced, and the drift increases, requiring a steeper bank angle. Initially, the bank angle necessary to maintain the synched azimuth may be almost close to zero. Later on, it increases exponentially rather than linearly. The cue to turn to pure pursuit is 30° AoB.

The turn towards the target’s RQ – rear quarter – deserves a more in-depth discussion. However, generally speaking, 45° of bank angle should be OK. Nevertheless, VC and the Phantom’s speed dictate the turning radius and its effectiveness. Therefore, if by assessing the closure, the crew observes they are intercepting a fast aircraft, then beginning the turn at 10 nm is suggested. Otherwise, 7 nm is a solid option.

That being said, DCS is a game with a vastly dishomogenous audience. You can work out your own technique, for instance, modifying the sync angle or the AoB of the conversion. Often, pulling a hard turn to pure pursuit will result in a less elegant but faster rollout behind the target.

Conclusions

The Sync-Z-Turn is a fantastic technique useful to seasoned and ad initio players alike. With only a few hours of practice, it can be learnt and understood very well. Moreover, it applies to any aeroplane featuring a b-scope, such as the Mirage F1, although modern fighters equipped with Track-While-Scan or equivalent and Datalink can use other procedures.

Before wrapping this up, let’s recap and add more features of the Sync-Z-Turn to the items listed at the beginning of the article.

- Given the simplicity of this technique and the fact that only the synched azimuth is the only variable, comms between Pilot and WSO are vastly reduced. For instance, a simple “Sync 45 Left”, or Right, or Port/Starboard is sufficient to initiate the Sync-Z-Turn. This is where this procedure’s name originates from;

- The APQ-120, the AWG-9, and other radar systems are affected by jamming. In DCS, they can still angle-track the source of the emissions, thus providing azimuth and elevation. The Sync-Z-Turn can be successfully employed against such a target, using the jamming strobe as a reference, until the range decreases below the burn-through range;

- The Sync-Z-Turn can be used with or without radar lockon. In DCS, where RWRs are often overprecise, avoiding a lockon can benefit the fighter, especially against a human opponent. Moreover, a smart WSO can intermittently paint the bandit just enough to monitor the progression of the intercept, thus denying even more awareness to the target;

- Changes in geometry, symptoms of a bandit becoming aware or manoeuvring, are immediately observable by changes in terms of drift and the related bank angle needed to continue the Sync-Z-Turn. By assessing whether the angles are increasing or decreasing, the Phantom’s crew can determine whether the bandit is turning hot or cold.