When the JF-17’s pilot wants to engage and employ a missile against his targeted group, they can access two main radar modes: STT and SAM. Heavily simplifying: “hard” lock and “soft” lock.

STT stands for Single-Target Track. The radar is solely focused on the locked target, which can cause the bandit’s Radar Warning Receiver to alert the crew. The RWR, in fact, can detect the changes in PRF and other parameters associated with STT.

The alternative is SAM, acronym for Situational Awareness Mode. SAM allows target tracking and engagement without entirely focusing the radar on the target. Therefore, the target’s RWR does not alert its crew.

SAM is initiated from either Range-While-Search or Track-While-Scan by “bugging” a displayed contact. In other words, by selecting it with the cursor on the radar display.

If the JF-17 pilot wants to engage more than one target at once, they can “bug” an additional contact, and the radar mode automatically switches to DTT, or Dual Target Tracking mode.

“Bugging” further the primary target, the radar switches to the familiar Single-Target Track.

In-game: STT

For decades, until the arrival of AESA radars, single-target tracking was the most common means of engaging a target. Since the radar is focused on the contact, information is updated faster and with greater accuracy and reliability. Note that the PRF cannot be changed once STT is established, so plan ahead.

Unfortunately, STT is not common in DCS, and it is often avoided in favour of Track-While-Scan or equivalents or EODs such as IRST. Not only that but locking an AI aircraft in STT causes it to react immediately by activating its ECM equipment. Moreover, there is an argument against the capability of certain RWRs to even detect CW or PD STT tracking and missile guidance.

The emphasis on “stealth engagements” in DCS, therefore, limits the depiction of STT.

In-game: SAM

SAM provides two submodes, ASM and NAM, acronyms for Automatic Situational Mode and Normal Awareness Mode. The main difference between the two is who has control over radar parameters such as bars and azimuth. In ASM, those variables are automatically adjusted by the FCR system to increase the target refresh rate. In NAM, instead, the pilot has greater control over the radar parameters.

In a sense, ASM is somewhat similar to the APG-70 HDTWS, or High Datarate Track-While-Scan, whereas NAM is closer to Range-While-Search. Unfortunately, as mentioned, the game’s radar simulation does not penalise low frequency of refresh radar modes.

SAM mode allows the pilot to “bug” and track and employ two contacts at the same time, with the KLJ-7 automatically switching to DTT mode. The first “bugged” target is labelled HPT, and the second SPT.

STT and SAM: Performance study

Given the points just raised, why would anyone use STT over SAM? Simply put, STT is, in theory, more reliable and accurate and, therefore, gives your missile the best chance to connect. To verify and quantify the advantage of STT versus SAM in this regard, I put together a simple test: a Tomcat is flying perpendicularly to the Thunder following a racetrack pattern. It starts from left to right and proceeds anticlockwise. This means that the F-14 enters the mainlobe clutter area, leaves it, and then proceeds to enter the zero Doppler interval. This is a tough situation for any radar, so let’s see how they fare.

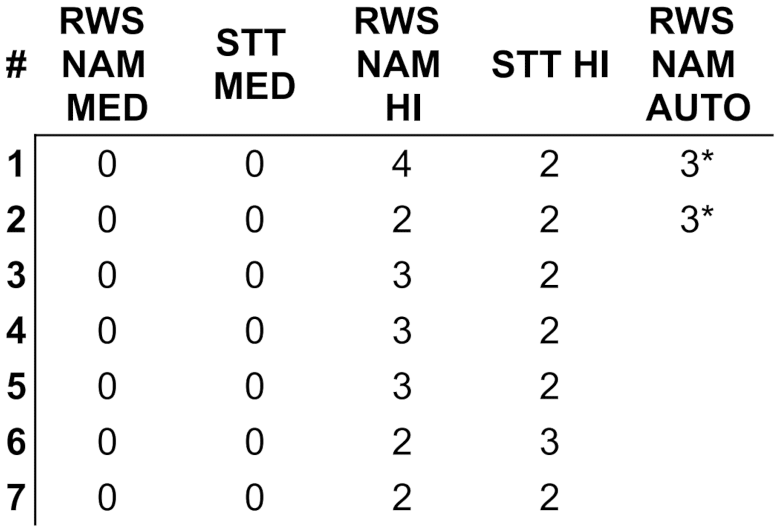

This table shows how many times the lock was broken during the anticlockwise pattern from left-to-right, and then right-to-left. Medium PRF offers solid performance no matter the mode used, whereas STT is slightly more reliable in High PRF.

*contact visible in RWS but cannot bug the return.

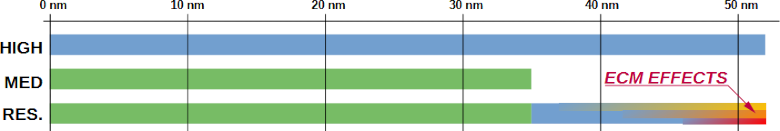

So, as long as the range and altitude allow MPRF, there is no reason not to use it. Medium Pulse Repetition Frequency, in fact, is often considered an “all-aspect” radar mode and it is more apt to track manoeuvring targets. However, as discussed in the previous article, High PRF and Medium PRF have different detection ranges. It is in the range interval between the two that opting for STT may improve the tracking of a target. This is, however, not always true, as an ECM-capable target located beyond burn-through range may react and break the lock anyway. Unfortunately, it comes down again to the stealth emphasis of DCS.

At the end of the day, the pilot has to choose how to engage their target, but knowing the differences between STT and SAM is fundamental.

Note on multiple engagements

As mentioned SAM RWS, both NAM and ASM are locked to ±30° of azimuth. Ergo, targeting two groups with a considerable horizontal separation can be challenging.

TWS DTT instead allows the pilot of the JF-17 to bug two contacts as long as they fall within the constraints of Twiz itself. In other words, if you see the targets, on your radar scope, you can track and engage them.

So, which one should we use? Again, it depends on the pilot’s level of Situational Awareness, the defined game plan, etc.

As mentioned in the previous article, Track-While-Scan offers more information, which is always useful to the pilot.

Supersearch

Before wrapping this up, I noticed that the KLJ-7 FCR of the JF-17 enters a peculiar mode when the **acquisition button is depressed. This mode, often called “supersearch” in many other modules, forces the azimuth to a very narrow interval, whilst the bars are extended. This mode is particularly handy as working with azimuths is usually simpler than elevation.