This article discusses the F-14 Tomcat from the perspectives of Thrust-to-Weight ratio, engine performance versus altitude, payload, and fuel consumption.

NOTAM

Given the amount of data I collected, I had to break down the analysis into different videos and articles to make it more digestible. I decided to start, hardly breaking news, from the F-14 Tomcat.

Before starting, shoutout to all my supporters from Patreons, other means, and all the friends on Discord. Without your support, I could not justify the cost of buying the modules I then test. Thank you!

Reference Data

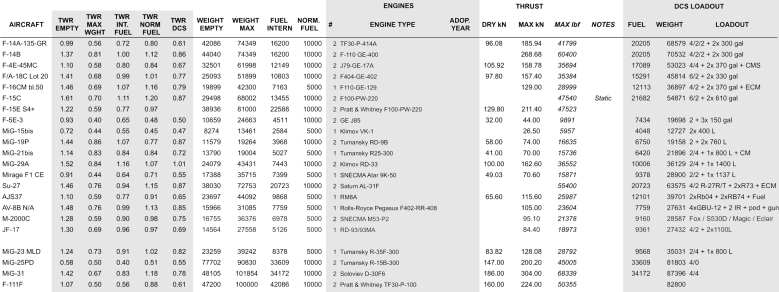

This table shows the technical data of the F-14A and other aircraft. What immediately catches the attention is the astounding weight of the Tomcat. Although not stellar, the thrust provided by the TF-30s is reasonable and actually better than others. Unfortunately, when paired with the obese F-14, the resulting TWR is mediocre at best.

The F-14B, discussed after the F-14A, features a pair of F110 engines. This upgrade arrived quite late in the life of the Tomcat and was applied to a reduced number of aeroplanes.

Test Payload

The test setup I opted for is the standard 4/2/2, with and without full fuel tanks. Ergo, four massive AIM-54 Phoenix loaded in their dedicated supports in the “pancake” area between the engines, plus two AIM-7 Sparrow and two AIM-9 Sidewinder in the external stations.

The internal fuel is normalised as usual to 5,000 lbs per engine, bringing the total to 10,000 lbs.

The clean jet still features pylons, if present in the default configuration, and the fully loaded internal gun.

The F-14A-135-GR Late

This version represents a mid-90s onward upgrade of the F-14A introduced in 1974, featuring the AN/ALR-67 Radar Warning Receiver and the LANTIRN pod. Besides those features and other minor details, it resembles the late 70s to early 80s 135-GR Early. In particular, it still features the infamous Pratt&Whitney TF-30.

One of the very first turbofan engines, this should-have-been temporary solution, was ported as a cost-saving measure from the failed F-111B. Although capable in many regimes, the TF-30 suffered in the high-G world of fighter jets, being prone to stalling when the manoeuvres disrupted the airflow intake. The peculiar design features of the F-14 Tomcat exacerbated the issues caused by the loss of an engine, and it cost a lot to the US Navy, both in terms of materiel and lives.

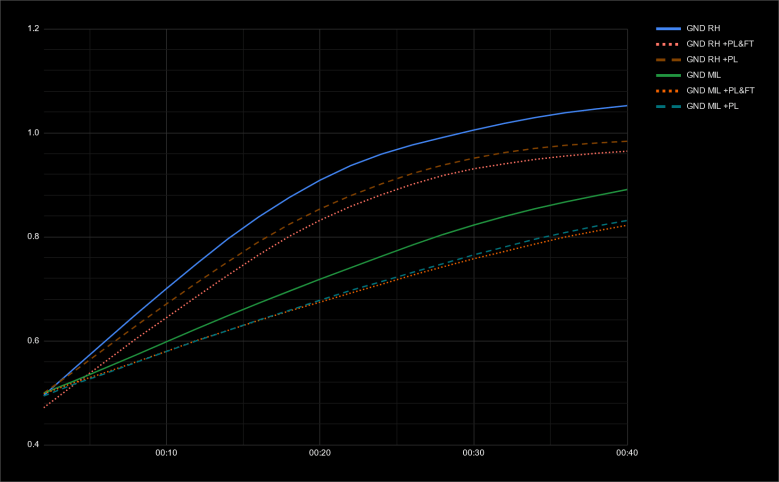

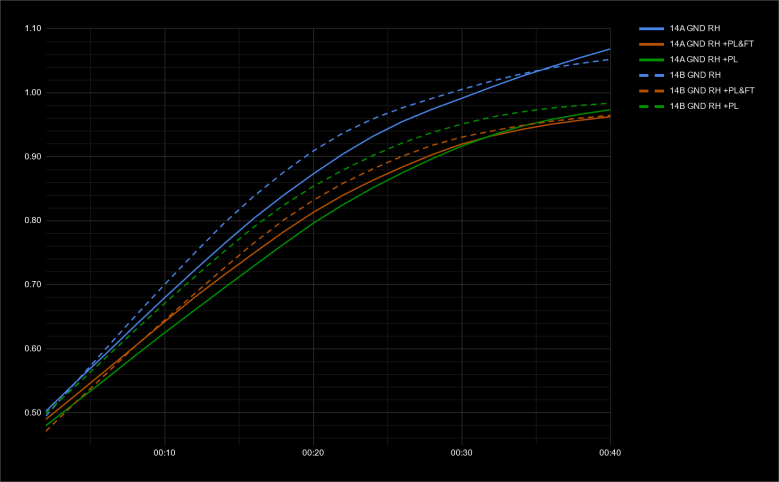

Ground-level Performance

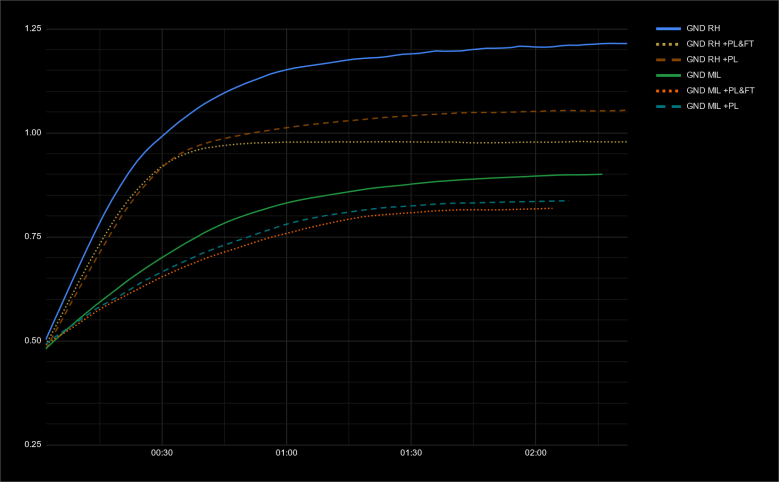

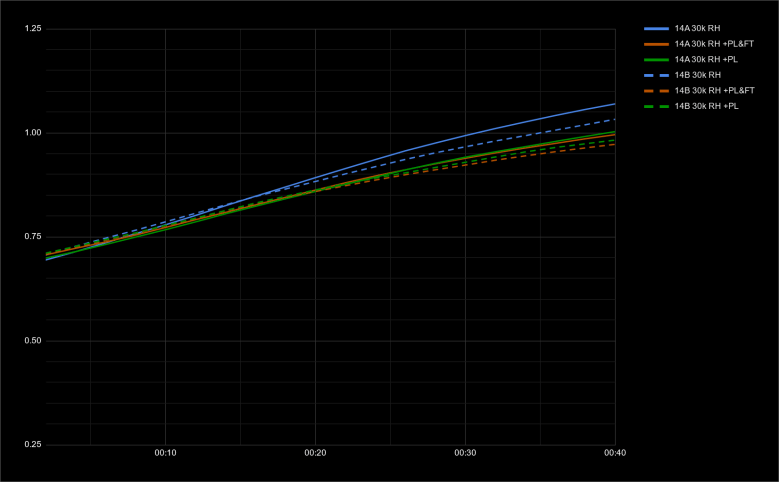

The first set of charts, all representing speed (Mach) vs time (s), shows the performance of the F-14A at ground level both in military and reheat. Since this is not a Fly-by-wire aeroplane, I may have dipped momentarily into the ground effect area, but only momentarily.

The “P” suffix stands for payload, and “PFT” for payload and fuel tanks.

At ground level with full reheat, the F-14A is fast. Like, really fast, topping at Mach 1.21. The F-15C arrives close to the Tomcat, but the Eagle is 30% lighter, a non-ignorable difference, and slightly smaller. Out of the 16 aircraft tested in this scenario and discussed in another article, only the smaller MiG-29A is faster and reaches Mach 1.22, but with a lower fuel load since 10,000 lbs simply do not fit and an empty weight over 40% lighter.

So, what is the secret here? Well, as it turned out, the TF-30 had extremely interesting characteristics. The lack of electronic controls and its quasi-ramjet behaviour meant that the more air was fed into it, the more it pushed. Peculiar solutions like the sweep wings also allowed the Tomcat and the F-111 to reach otherwise unexpected speeds. The cons is a fairly poor acceleration, especially compared to ad hoc fighter-jet-designed engined, and when the afterburner is not used. The curve when Military setting is used, in fact, is quite smooth and nowhere near as aggressive as the Reheat curve.

When ordnance is loaded, the F-14A can still push through the transonic speed, but the addition of the external fuel tanks prevents the Tomcat from reaching supersonic speed. If the altitude allows, a minor unload should be sufficient to break through the transonic region.

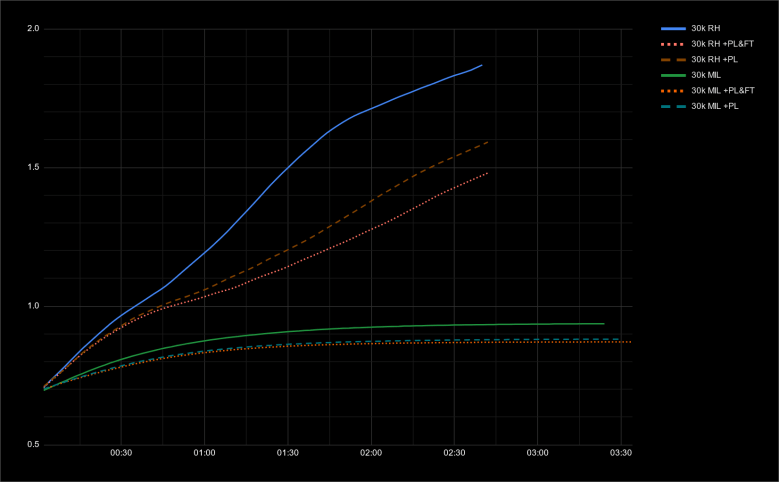

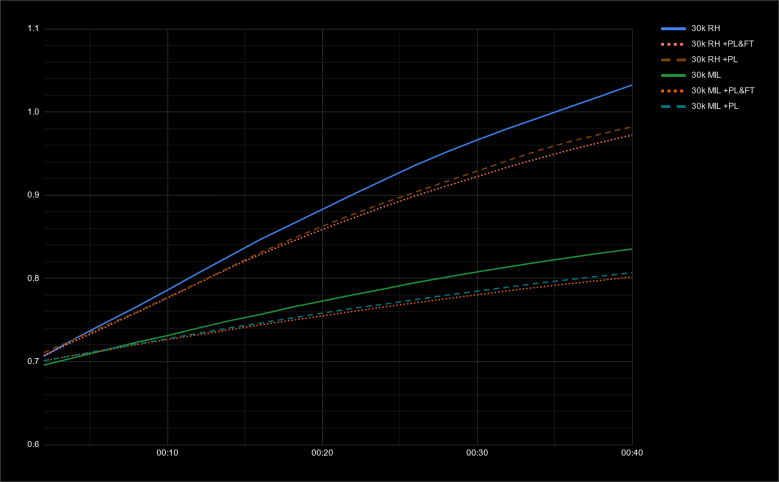

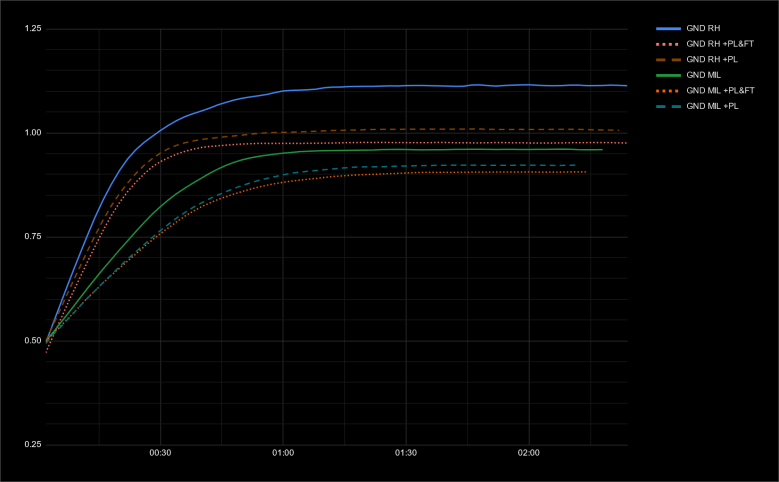

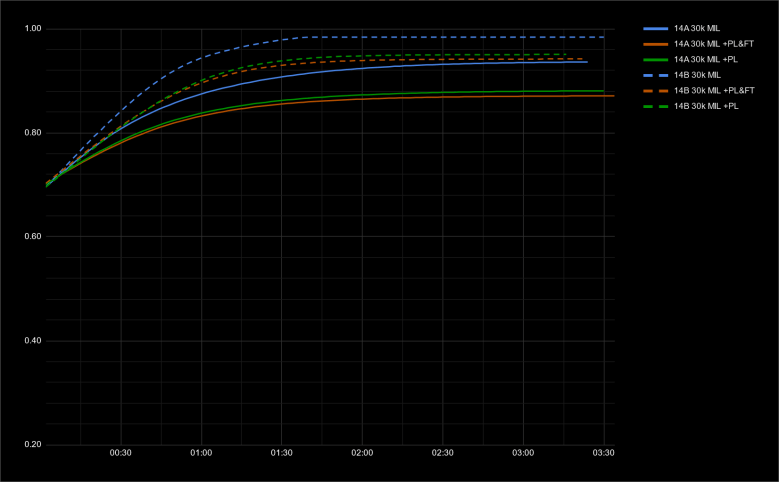

High-altitude Performance

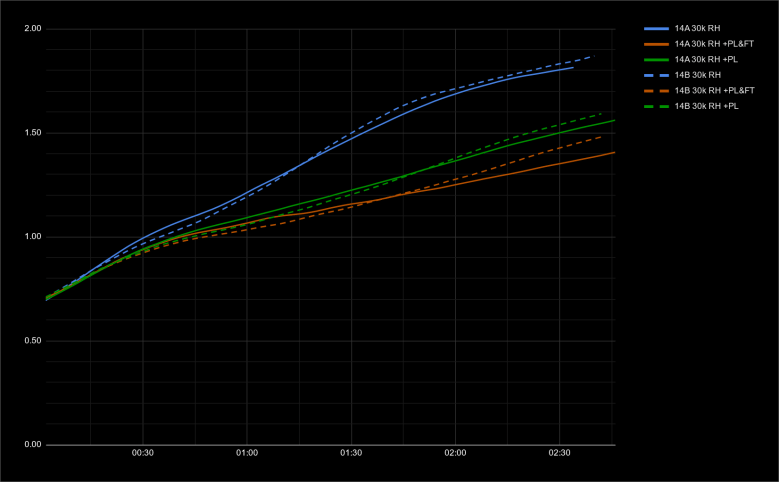

At 30,000ft, a clean F-14A reaches very high speeds. The envelope is only marginally affected by the transonic region. Past that, the acceleration starts to attenuate only past circa M1.7. The presence of external payload and fuel tanks affects the overall performance, but not as much as we may expect. The additional drag and weight are a tangible factor, once again, throughout the transonic region.

Unfortunately, the F-14A cannot supercruise, ergo fly at supersonic speed without the afterburner selected. The acceleration in Military is once again a bit sluggish, even in clean configuration. Interestingly, the presence of fuel tanks is almost a non-factor speed-wise, whereas their impact was clearly observable in the other scenarios.

F-14B

Formerly the F-14A+, the Tomcat-B saw the introduction of a new engine, vastly more suited for a fighter jet. Although this upgrade should have been deployed shortly after the launch of the Tomcat, with the first tests on alternative engines dating to 1973, budget and other reasons pushed it to the early to mid-80s, and only a fraction of the Tomcat fleet received the new General Electric F110.

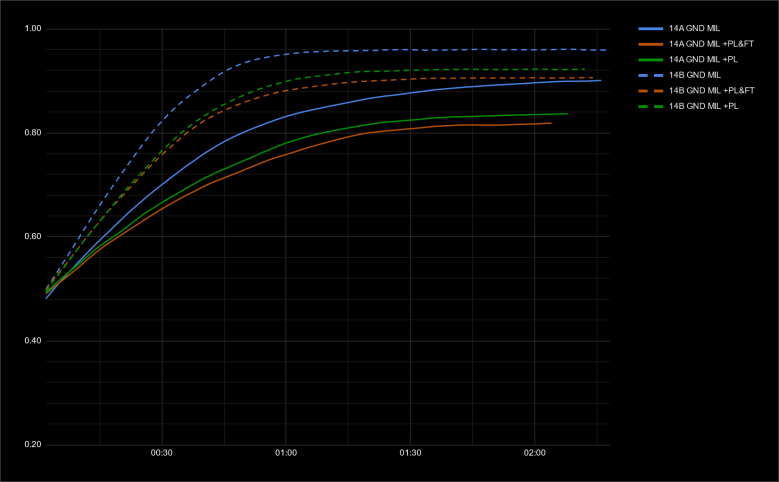

Ground-level Performance

At ground level, the barrier represented by the transonic region is penetrated only when afterburners are employed, as the shockwaves produced as the aeroplane reaches the speed of sound require more thrust to be tamed. The presence of external stores, even the “4/2/2” configuration without fuel tanks, see the F-14B struggling past Mach 1. The situation is even more exacerbated when the “bags” are added.

At military power, the F110s provide good thrust and acceleration, with the corresponding curves raising quite steeply until the transonic region is hit at circa Mach 0.8. Once again, the difference between having fuel tanks on board and only air-to-air weapons is not that drastic, so if you have ever wondered whether increasing drag and weight is worth the cost of loading two “bags”, then the answer seems to be a solid “yes”. More on this later, as we dive into the fuel consumption numbers.

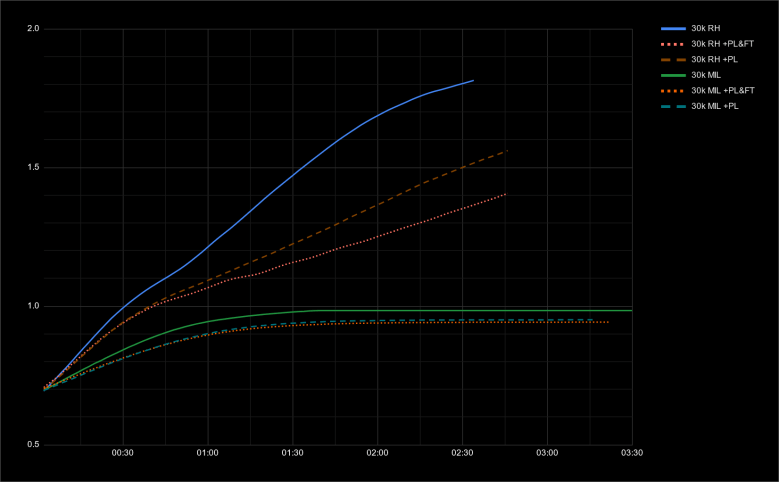

High-altitude Performance

Looking up high at Angels 30, we notice again how fast the F-14 Tomcat can be. The presence of external ordnance does affect the acceleration and maximum speed when reheat is used and the curves diverge as a function of speed. In military setting, instead, the difference is minimal when external ordnance is loaded onto the Tomcat but even the difference between these scenarios and a clear aircraft is quite marginal.

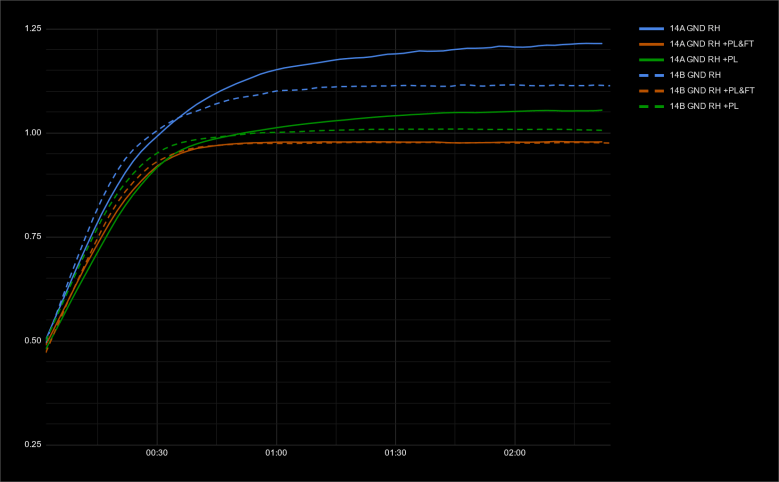

F-14A vs F-14B

Now that the general characteristics of the F-14A’s TF-30 and the F-14B’s F110 are more defined let’s compare the two Tomcats directly, starting from the Ground plus Reheat scenario.

This chart shows a curious situation: the F-14B shows better subsonic acceleration, whereas the F-14A wins and takes the crown past the transonic region. Interestingly, the F-14A’s pattern persists, and the F-14B settles at stable speeds. The 40-second detail shows the difference even better and, even accounting for the data-gathering tolerance of ±0.02 Mach, the F-14B is clearly better. This peculiarity means that the F110 are a better tool for combat situations requiring speed regime changes, as it provides greater acceleration. If the task is closer to an “old school” intercept where speed matters than the TF-30 is a surprisingly capable engine.

The military thrust perspective overturns the previous considerations. Here, the F-14B easily dominates by a long margin, no matter the aeroplane configuration. The Tomcat-B pilot has vastly more power under the hood and can sustain manoeuvres and regime changes without resorting to the afterburners, which are terribly expensive fuel-wise.

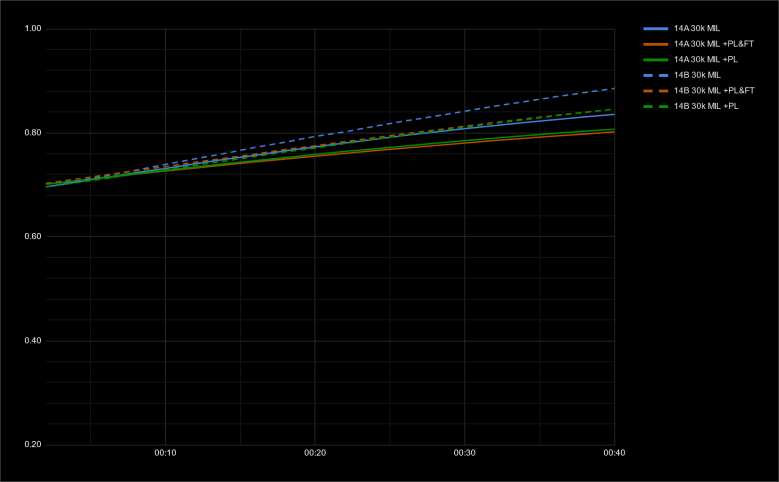

At 30,000ft, the music changes again. Although all the curves are fairly comparable and close to the margins of error, a trend is observable: the TF-30 seems to have an ever so slight advantage throughout the transonic region, but then the GF-110 shows its muscles, providing a little more boost no matter the loadout.

Lastly, the 30,000ft in military thrust setting scenario reminds us of the corresponding test at ground level. The difference is not as tangible, but the F-14B reaches and sustains higher speeds quicker than the F-14A. Once again, this capability is very handy, as it allows the Tomcat-B to sustain manoeuvres and react to different situations without resorting to the afterburners.

Fuel Consumption

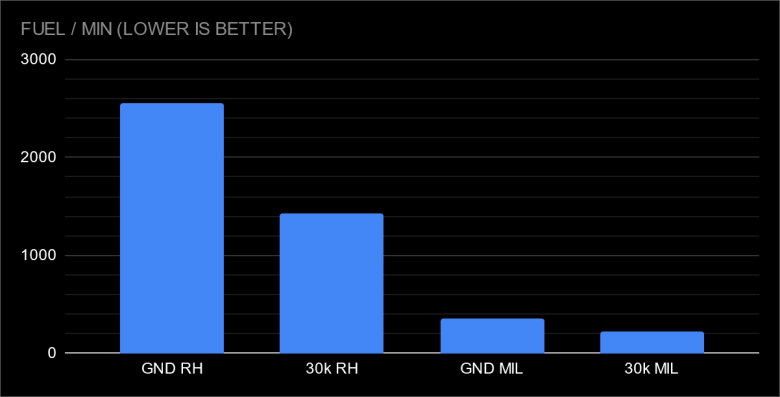

So far, the discussion has been exquisitely focused on the speed and acceleration side. But, what about fuel consumption? Getting to Mach 2+ is all fun and fancy, but how long can a fighter sustain such engine settings? The following charts show the fuel, in pounds, used per minute and per hour. The white line represents the maximum fuel load with the payload selected for this test, with the internal quantity maxed and not normalised to 5,000 lbs per engine. For both F-14s, the quantity is circa 20200 lbs.

Combining this chart with the previous highlights some fascinating facts:

- In primis, at low altitude plus reheat, the F-14A is incredibly fast and, surprisingly enough, consumes less fuel than the F-14B, circa 10% less. Although reheat is not sustainable in the long term, with a theoretical endurance of circa 7-8 minutes, this characteristic allows the F-14A to sprint faster and slightly longer in case the crew deems it necessary.

- Remaining down in the weeds, the Pratt&Whitney and the General Electric engines perform identically at military thrust settings but, as we have seen, the F110 propels the Tomcat-B faster, allowing it to sustain M.9 in military even in dirty configurations. So, changing perspective, it means that the F-14B uses less fuel to maintain the same speed as the F-14A while providing more significant acceleration.

- Up high, the performance envelopes at military regimes mimic the situation down in the weeds: the F110 provides greater speed at comparable fuel consumption. When the afterburner is engaged, however, the situation changes as the TF-30 does not “run away” as it does at low altitudes. Instead, the F110 manages to keep Grandpa P&W’s pace and even overtake it past the transonic region.

Conclusions

I hope this first discussion about thrust-to-weight ratio and aircraft performance is valuable and interesting to you. I have conducted a similar series of tests in the past, but none have been as deep and extensive as this one, with hundreds of thousands of data points collected.

Personally, I now see the TF-30 in a different light: imagine this engine powering an F-111 Aardvark. It certainly lacks acceleration, but it pushes for days with this aeroplane’s 30,000 lbs of internal fuel and allows it to dash at ludicrous speeds if required. Ergo, fly at a fairly sustained speed, and it will do wonders. It enables the Tomcat to unload and bugout or blow through at low altitudes with very, very few opponents (and missiles) capable of chasing it down.

On the other hand, start tossing your jet around, and you will have issues.

The GF-110 instead is a real fighter jet engine. Perhaps it won’t shine in some specific situations as the TF-30 at low level, but it overall offers vastly better control, greater acceleration and performance even without the usage of the afterburners.