After the recent content mini-drama, I watched the video in question and found… “inaccuracies”.

we want to ensure that we are the ones to shoot first and that’s why in a fox one fight the employment and crank phase is critical because we want to make sure that we have two sparrows out on each bad guy so in a 2v2 we want to make sure we have a sparrow out on both of the bad guys because ideally if we can shoot first and get them defensive then we can get closer to them and take a second or maybe even a third shot at a much higher probability of kill and actually shoot them down.

Does that make sense?

Well, the answer is NO.

Real-life account

Now, jokes aside, the principle per sé is not incorrect, and there are situations where it does work.

However, this is usually not the case. Let’s watch this account from the always brilliant Aircrew Interview.

So, Tornado F3 with freshly delivered AIM-120s go for a grinder, but the clever Dutch understand their gameplay and simply drag the missiles. This means that all of them were defeated by turning cold or other manoeuvres.

The Tornado ADV, Air Defense Variant, is the fighter version of the famous low-level strike aircraft. Despite being one of the fastest fighters down low, it struggled at high altitudes and was not as manoeuvrable as other “native” fighters. Nevertheless, the late Tornado ADV was a very capable aeroplane: it had an excellent radar, AIM-120 AMRAAM and was one of the first to receive LINK16 capability.

Eventually, the Tornados run out of AMRAAMs and get, understandably, slaughtered in the merge. This is, from a real pilot, the simplest way to describe my greatest issue with the idea of throwing missiles at ineffective ranges and praying to the lord and Saviour you fancy the most, especially at the edge of their envelope.

Before moving forward, it is worth remembering that cranking, notching, or dragging can indeed be used as defensive postures, but a seasoned player will use them consciously. Ergo, they do not mean “running away”, as the idea of “forcing to defend” would suggest. On the contrary, they are executing their gameplan, wasting your missiles and waiting for an opening to strike back.

- CRANK [direction].

[A/A] Maneuver in the direction indicated. Implies illuminating target at or near radar GIMBAL limits. - NOTCH(ING) [direction].

[A/A] [A/S] [S/A] Aircraft is in a defensive position. Maneuver(ing) with reference to a threat. - “DRAGGING” refers to DRAG [cardinal direction].

[A/A] Contact aspect stabilized at 0–60 degrees angle from tail or 120–180 degrees angle from nose.

Source: ATP 1-02.1/MCRP 3-30B.1/NTTP 6-02.1/AFTTP 3-2.5

More brevities, organised by topic, are available here.

A matter of kinematics

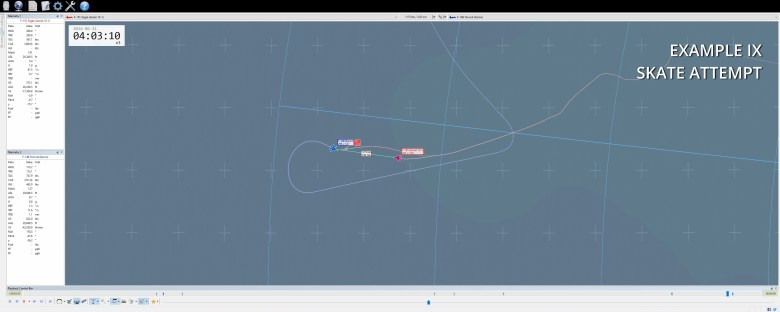

The FLO mantra falls apart the moment a seasoned player is on the other side of the fence. Before studying proper engagements, let’s start with something that, on paper, looks a bit silly. This is the very first test I flew. I was piloting using the keyboard because I simply wanted to see if the setting was meaningful. There is so much wrong with the Tomcat engagement, but I decided to keep it anyway, as it makes for an exceptionally good, bad-case scenario.

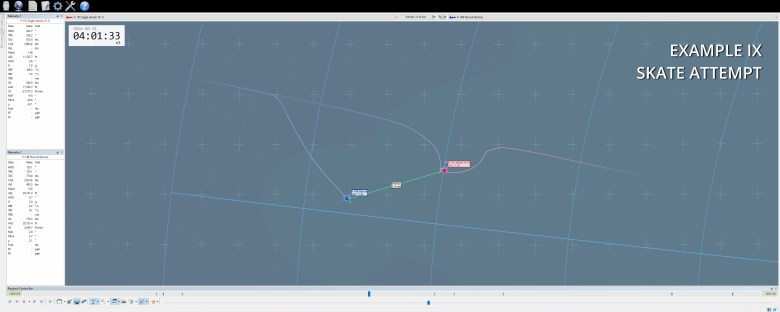

I was flying a Tomcat versus a Phantom. Both were armed with a pair of AIM-7F. The AI shot at 20 nm and a speed of M1.25. I wanted to wait until 15nm, but since I messed with the keyboard in the loft, I launched at 17.1 nm. I also forgot to crank up the throttle.

As you can see, both missiles were defeated. After cranking, I turned hot, dived again using Iceman, and launched a second AIM-7 that connected.

Something you may have missed is the distance and speed of each missile as they were thrashed simultaneously. The Phantom’s AIM-7 was at 4.72nm at a speed of M1.43. My Sparrow was at 4.12 and flying at M1.71. Not only was mine faster, but also closer when the Phantom defeated it. Let this sink in for a moment: I launched later and almost half a Mach slower, but my missile would have connected before the one launched earlier. After the data analysis, we will see more quick scenarios where I maintained higher speed, or where neither the Tomcat nor the Phantom defended.

Data analysis

Let’s get to everyone’s favourite part: maths!

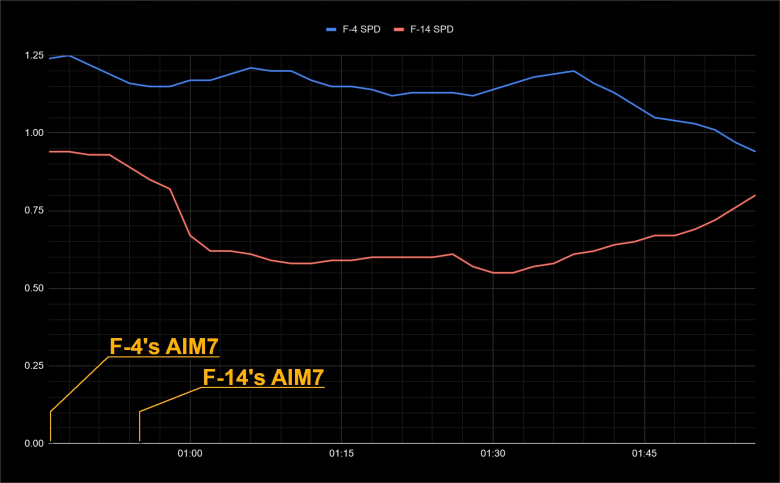

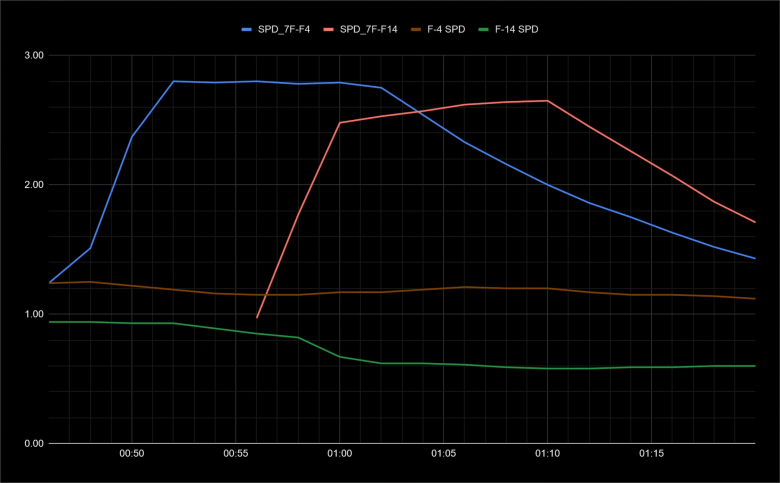

As mentioned, I forgot to crank up the throttle. The F-14 execution is ridiculous, launch speed around M.85, hitting a low of M.55 in the crank, which is *not* much at 30,000 ft! The Phantom instead maintained supersonic speed for the vast majority of the engagement, with a launch speed of Mach 1.24. That’s a stunning 30% advantage! The AIM-7 study I released a couple of years ago demonstrated the positive effect of speed over the Sparrow kinematics. However, this is only one of the many variables. Side note here: is it me or the AIM-7F is not lofting as much anymore?

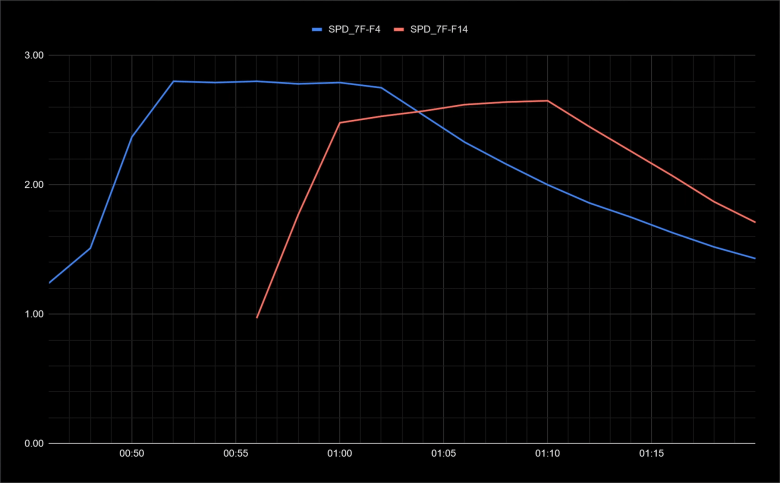

The second chart shows the speeds of the two AIM-7s. The envelopes are very similar, but the speed advantage of the Phantom’s Sparrow is extremely visible. In particular, it managed to reach and sustain the decent speed of M2.8 for 10s before slowing down. The effect of the Tomcat’s crank is visible as well in the missile speed-loss pattern.

The F-14’s AIM-7 instead reached the plateau at M2.55, and barely crossed M2.6 whilst diving on the Phantom.

Plotting both the fighters and the Sparrows’ curves together, from the first launch to the second missile thrashed, we see a few more interesting details. In primis, the speed of the F-4’s Sparrow remained somewhat stable even during the hard turn at the beginning of the crank. In other words, as long as the dual-thrust rocket motor was running, the Sparrow maintained a stable cruise speed.

The F-14’s AIM-7 instead slightly accelerated as it dived downwards. The AIM-7 had to fly through the thicker air as it chased the F-4, resulting in a drastic increase in drag. These two contrasting factors possibly negated themselves for a few seconds.

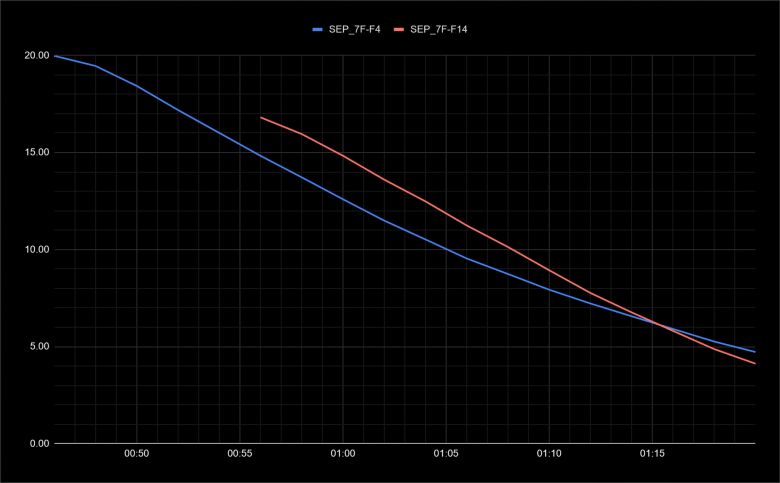

The last chart is the one that most clearly shows how the situation flipped, with the advantage, in terms of kinematics, switching from the F-4’s side to the F-14’s.

This chart represents the separation between missile and target over time. In other words, a distance equal to zero means that the AIM-7 connected. Neither did in this case, but the role reversal, so to speak, is appreciable at timestamp 1:15. If we add the fact that the Tomcat’s Sparrow was faster than the Phantom’s at the end of the chart, we can conclude that the 20nm employment by the Phantom was not an optimal choice, the plethora of issues from the F-14’s side notwithstanding.

The real issue here is the energy of every missile in DCS eventually runs out. Ergo, missiles have to cover the required distance usually without relying entirely on the energy accumulated whilst their rocket motor is active. If the target manoeuvres, the energy required grows exponentially.

A missile employed at shorter range instead, does not waste its energy peak covering the emptiness, and may reach the target faster and even sooner. On top of that, the second shooter may capitalise further and gain from the situation by responding immediately to the threat whilst improving the odds of success of their missile.

| SPD F-4’s AIM-7 | SPD F-14’s AIM-7 | |

| AVE | 2.17 | 2.2 |

| MED | 2.25 | 2.45 |

| σ2 | 0.31 | 0.25 |

| σ | 0.56 | 0.5 |

An interesting indicator of such behaviour is the comparison between average and median. From launch to the 1 minute 20 mark, the average speed of the F-4’s AIM-7 was M2.17. The speed of the F-14’s was M2.20. No matter the meaningful help of the far higher initial speed, the second AIM-7 still came out faster on average. However, it is the median that sheds more light on the outcome of the scenario: M2.25 for the F-4’s, and M2.45 for the F-14’s Sparrow.

Caveats

So, more or less identified the problem, let’s see some caveats and exceptions to the rule.

- The greater the difference between kinematics, the more shooting range becomes relevant and the timelines probably diverge. In such cases, shooting at the maximum possible range might even be a necessity.

- Similar observations apply to the avionics as well. For example, the SD-10 can outrange the JF-17 Thunder’s KLJ-7 radar.

- Guidance and missile characteristics further differentiate and drive the choices of the crews. In primis, ARH vs SARH. The Active Radar-Homing missile, often inappropriately called after the related brevity “FOX-3”, usually does not require the shooter to sustain the missile until timeout, providing a great deal of flexibility to the crew. Vice versa, the “FOX-1”, Semi-Active Radar-Homing, places more limitations on the shooter.

- As mentioned earlier, the rocket motor of a missile eventually stops providing thrust, and the missile decelerates. A technique to invest energy to increase range and speed exists: lofting. Some missiles take advantage of such capability by default, for instance, the AIM-120 AMRAAM or certain modes of the AIM-54 Phoenix. Other missiles can instead benefit from the shooter pitching up. Albeit in some cases probably unrealistic, this manoeuvre provides an upwards momentum to the missile, allowing it to reach higher, less draggy air, and then dive on the target.

- At the moment, only single and dual-thrust missiles exist in DCS. Unless I am missing something, that is. When the MBDA Meteor reaches these virtual shorts, things will change. The rocket motor of such a missile, in fact, is a throttleable ramjet, capable of sustaining the missile for a prolonged period. Simply put, the missile will be able to adjust its performance depending on the situation, thus remaining a threat even at very long ranges.

- Lastly, numerical superiority or inferiority drives the engagement tactics and, therefore, the engagement contracts.

Additional Examples

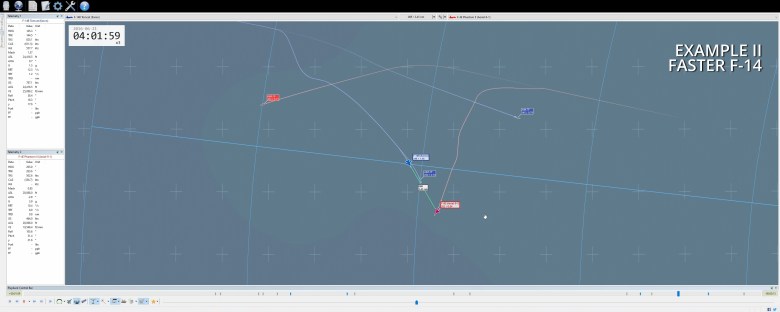

Faster F-14

This example is identical to the first, but I connect the stick first. I’m told it helps!

After spawning, full reheat and the gameplay is pretty much the same. Note how the Phantom dropped its Sparrow at a certain point. That’s because the AI does not evaluate the parameters involved in the fight.

This is also why the idea of launching at FLO kind of makes sense, as long as the AI is incapable of any reasonable and baseline tactics.

However, this is almost an exploit of the extremely poor AI that, as mentioned, falls apart the moment a human familiar with the very basics of this game jumps into the cockpit.

The next example tries to tackle this very problem.

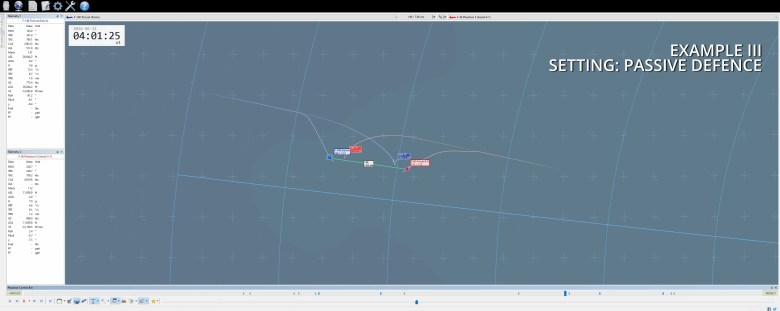

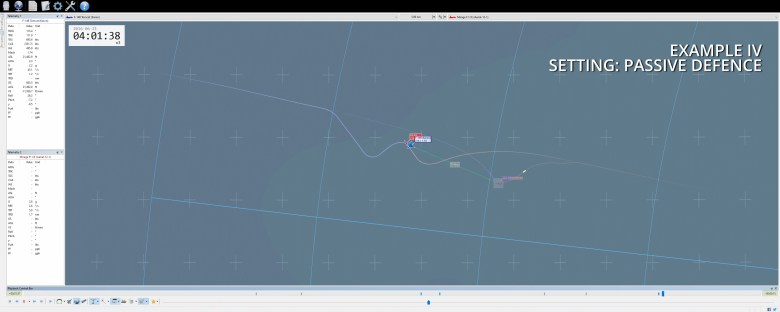

AI Passive Defence

Another example: this time, I wanted to adjust the AI to make it less exploitable. For this reason, I set them to passive defence, something I randomly did in my campaign as well to vary their behaviour and mimic different capabilities. The objective is to verify whether the AI will now sustain its missiles until timeout.

As appreciable from TacView, the AI’s Sparrow was defeated kinematically by a hard crank. My AIM-7 followed a similar fate. As happened in the previous examples, the AI decided to dive, perhaps a scripted behaviour, to help with the APQ-120’s restrictions. Something that probably does not even affect the AI, but it is good to see a more varied engagement.

Nevertheless, the AI’s missile was indeed a threat, and anything more capable than an AIM-7F could have created a headache for me. Conversely, in such a case, I would have used a different tactic. Still, it is good to see the AI mimicking human behaviour, not dropping their ordnance when unnecessary. However, now we have the opposite problem: the AI will not attempt to defeat any incoming missile kinematically anymore.

Different missiles

So far, all tests have shown a sort of mirror match between AIM-7s. Given the popularity of such a missile, this scenario is remote but not impossible. Think about the 1988 Operation Praying Mantis, in which the US Navy faced Iranian forces.

That being said, in DCS, the AIM-7 is more likely to face other threats, ranging from the R-27 to the S-530 and others. An extensive study about Cold War-era missiles can be found on these pages.

MATRA S530F

The French Matra Super 530F is carried by the Mirage F1. Performance-wise, it appears to be slightly more performing than AIM-7F, R-40 and R-27. In particular, it reaches a higher immediate peak speed and maintains energy better than the R-40.

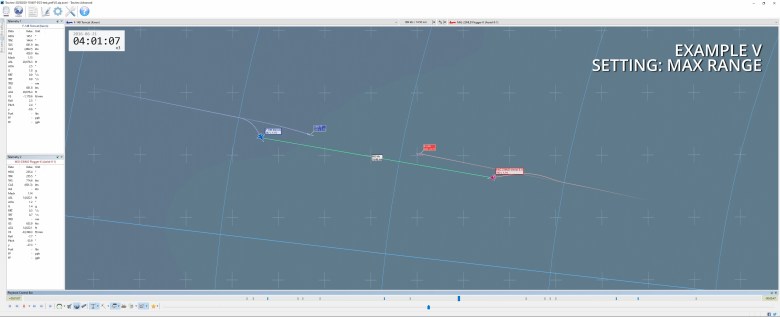

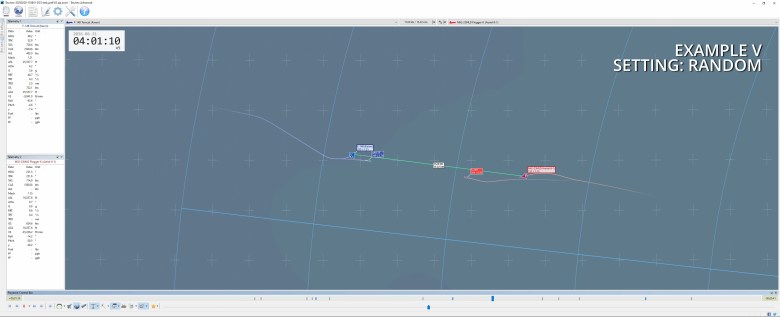

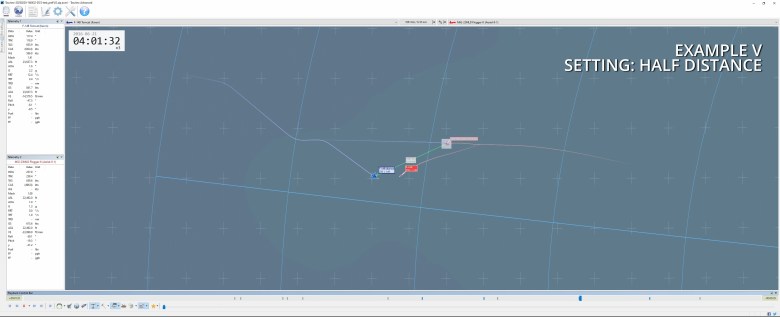

In this example, I engaged a Mirage F1 set to passive defence and maximum launch range.

The energy advantage is countered by the hard manoeuvres of the Tomcat, peaking at the unintended value of 12 Gs. Well, there is a reason why I sit in the backseat… Anyway, the point of this example was again show some of the drawbacks of launching at maximum range.

R-24

The Soviet R-24 is available in two versions in DCS: Semi-Active Radar Homing and IR-guided. This missile’s performance is quite odd.

Although the video I showed earlier and behind the mini-drama described it as close to AIM-7 Sparrow, in-game testing confirmed the unexpected behaviour observed months ago. As the charts show, the R-24R sprints to an eye-watering M4.3 within 8s, whereas the 7E and 7F lag behind.

However, the envelopes also tell an interesting story: due to its drag and the lack of sustaining propulsion after the first few seconds, the R-24R soon becomes a brick. Albeit more than capable of outpacing and outperforming the old AIM-7E, the R-24R is overtaken after 10nm or circa 25s. This margin becomes even thinner if the target manoeuvres.

Given the observations from the charts, launching an AIM-7 beyond 10 nm ± a buffer, depending on altitude and geometry, should allow the fighter to engage in relative safety. So, what is the point of launching at 25nm as the video showed?

Additionally, when the launching aircraft is set to employ at max range, the R-24 shows how bugged this missile is.

Only when the employment range is set to half distance does the R-24 start to become a vague threat.

R-27 and R-40

Developed to improve the performance of the R-24, the R-27 similarly comes in two variants. The R-40 is, instead, a much older missile carried by the Veteran MiG-25.

Compared to the AIM-7P, the R-27 and R-40 feature a more explosive acceleration. Its characteristics closely mimic the R-40. In both cases, after 8s, the rocket motor quits, and the missiles are left with whatever energy they accumulated. After circa 15s-16s, the AIM-7P catches up with the R-27 and R-40 speed-wise and maintains the advantage from this point forward. In terms of distance covered, the Sparrow lags 2-4 seconds behind the competition, which is a value easily cancelled by superior manoeuvring.

In this example, I faced a Su-27 configured in the usual manner, followed by a MiG-25. Also, a quick note about the video: MiG-25 and MiG-31 are not “Mach 3+” threats. They can get to such speeds, but then they need to throw their engines into the rubbish, and the airframe itself may require thorough investigation.

The other side of the barricade

The video mentioned earlier assumed a huge asymmetry and advantage of the fighter. His F/A-18C was, in fact, carrying AIM-7P and the target loaded the forever-bugged R-24. What happens, instead, when we face an opponent with a longer reach than us? In this case, I am facing a MiG-25 armed with a pair of R-40s in the trusty F-4E carrying a pair of AIM-7E.

Here, I capitalised on the sensibility of older missiles against Gs and the considerable drag of the R-40. However, a much safer tactic may be taking an offset, thus reducing VC, until the range suits the AIM-7E. To counter this, the MiG-25 should have placed the Phantom on the hot side of their scope and worked our Target Aspect down. This manoeuvre, however, would have exposed them to us turning hard into them and launching a Sparrow.

The purpose of this theory crafting is to reiterate and highlight how employment range is just one of the many variables. A longer reach is nice to have, but geometry is overwhelmingly more important.

Range, Timelines, Gameplans

As the examples have shown, launching at FLO-range to force the target to defend is not necessarily a good game plan. Quite the contrary, sometimes. However, range is a factor when we look at the engagement from another perspective: modern Timelines.

Although Timelines were taught in schools such as TOPGUN already in the 80s, they appeared in public documentation much later, and even later, they have become a familiar concept to us gamers. By the way, I hope I have helped in this regard!

Back to the main topic, when Timelines and AIM-7s are discussed, we inevitably encounter a problem. As a former F-4E WSO brilliantly put it once, the AIM-7E and 7F were considered de facto all-aspect AIM-9s. Ergo, relatively short-range missiles, even the 7F.

The video in question tried to justify long-range employment with the idea of executing a launch-and-leave tactic. But, given the relative short range and mediocre characteristics of the Sparrow compared to modern missiles, this plan can leave the fighter in a perilous position.

Let’s see an example: F-14 vs F-15, both armed with AIM-7MH.

I launched at 23nm. The AI, as usual, did not defend as much as it could have but still managed to defeat the AIM-7. When I turned cold, however, I had circa 7-8nm advantage and a meagre opening VC. At circa 10nm, I turned In again, but at such high VC and short range, there was no time to find, lock, employ and more importantly, the odds of defeating the incoming missile were very low. An AIM-120 or AIM-54, instead, would have allowed me to turn cold much earlier as the missile’s seeker would have taken over. Alternatively, if the fighters operate in a Section or more, as they should, they can use a grinder to keep the hostile at bay. With some caveats, as we have seen.

The second example is exaggerated: a 35nm shot. As TacView shows, the AIM-7MH does not have the performance needed to be a threat. The AI defended and chaffed momentarily, but it could have thrashed it simply by insisting in their CC towards my Tomcat. Would a 30nm be more dangerous? No, not really, or at least not in this scenario. The AIM-7, in fact, became slower than the F-15 when the aeroplane separation was more than 16 nm.

This particular example raises additional points:

- In primis, EW. I had to set the F-15’s ECM to off. Otherwise, the burn-through range would have been around 23nm;

- It is hard to assess when the AIM-7 connects, is close to, or is still a threat to the target. In this case, I maintained my STT lock all the way through until I heard the F-15 locking me. Note that more modern aircraft may have a timeout indicator.

Different tactics

Tactics applicable in a video game are unlimited for obvious reasons. In the examples shown so far, the most straightforward technique was to turn to place the hostile at the radar gimbal limits. This reduces VC and increases the ratio at which the missile loses energy.

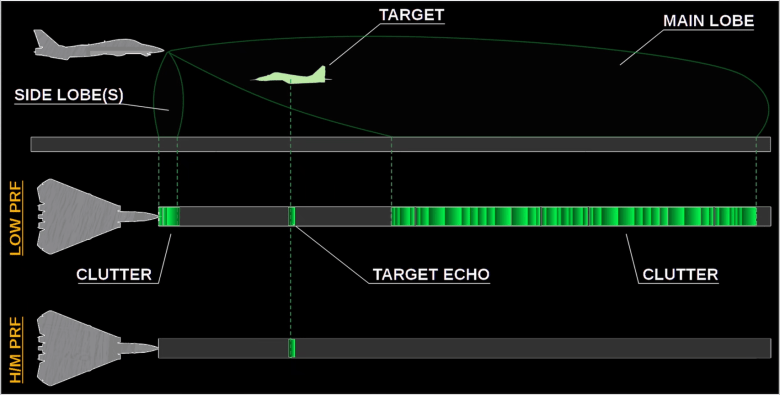

Another plan is to introduce a vertical displacement of tens of thousands of feet. If the adversary does not have the lookdown-shootdown capability, this measure should make the acquisition of the fighter much harder, with the usual caveats regarding how the main lobe intersects it.

In addition to the previous, as the target is “spiked”, it can try to turn into the beam and notch the illuminating radar. This method breaks the lock if well executed, with a caveat, once again, about the nature of the illuminating radar, as only Pulse Doppler radar can be affected.

Back to the topic, speaking of small realisations, an engagement flow I made up, and I was happy to hear it was sometimes practised in real life, is the AIM-7 into a conversion to enable a rear quarter AIM-9 employment. I discussed this on FlyAndWire.com extensively, and an in-depth study is available on the website.

The reason why I put it together, was to find a solution to translate a high-VC situation, preferred by the Sparrow missile, into a rear quarter that is necessary for older AIM-9 Sidewinder. The public documentation, being extremely introductive, puts a lot of emphasis on conversions. This suits well non-all-aspect Sidewinders. The Sparrow is a well-known missile, and I recalled how the Iranians managed to be twice more successful than the americans during the Iran-Iraq war by preferring front-quarter employment. This is when it dawned on me. All I did was put the two things together.

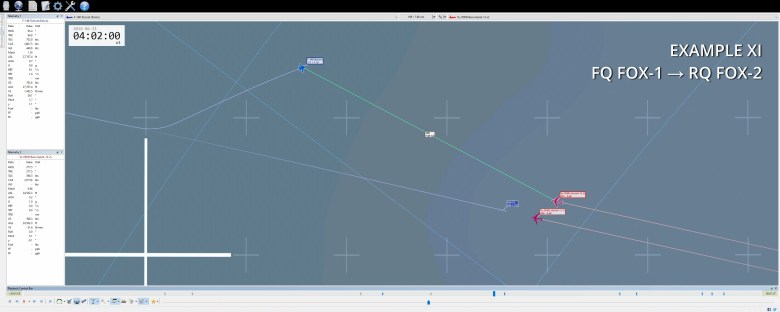

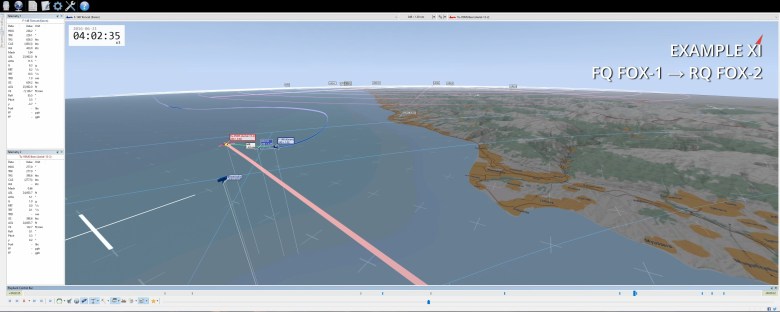

So, given all that was said and shown up to this point, and how launch-and-leave gameplans may be hard to achieve, especially when equipped with AIM-7E and AIM-9 pre-L variant, let’s see an example of FQ AIM-7 RQ AIM-9. Ergo, Front quarter Sparrow followed by rear quarter AIM-9.

After a FOX-1 at the usual 15 nm, hard left to start grinding down the aspect. In this scenario, achieving the canonical 40,000 ft of lateral separation is a bit of a chimaera, but fighter jets should be able to sustain a high-G turn to rollout behind the target. Given the short range, techniques such as the SYNC-Z-TURN should work well. If you are unfamiliar with this method, check FlyAndWire.com and YouTube channel, where the SYNC-Z-TURN was described and reinvented to suit many other aircraft.

The elephant in the room is the reaction of the hostile aircraft. This is where this approach struggles against the all-knowing DCS AI, whereas it can still work well, and I am speaking out of experience here, against human players.

Adding a vertical offset can also help avoid being spotted. Similarly, using an offset to stay outside the target’s radar scan volume can affect their situational awareness. Just remember to centre the T or turn to lead collision before employing it to maximise the missile trajectory by minimising corrections.

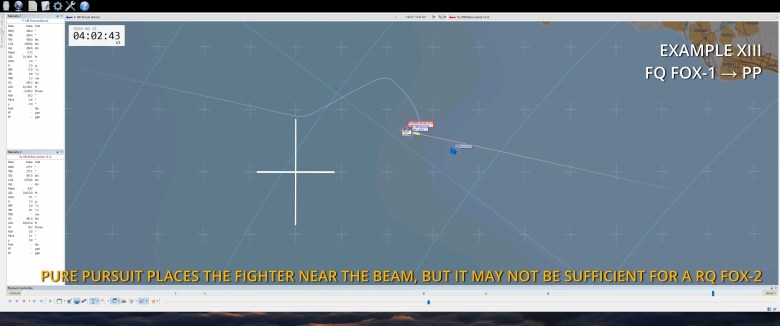

Location, location, location

A recurring and often ineffective play of new virtual crews is not developing their plan past the AIM-7 employment. This is one of the most common issues, along with sticking to Pure Pursuit from Commit to timeout. As discussed many times, even something as simple as a Collision Course is usually vastly more efficient in terms of time, resources, missile kinematics, et cetera.

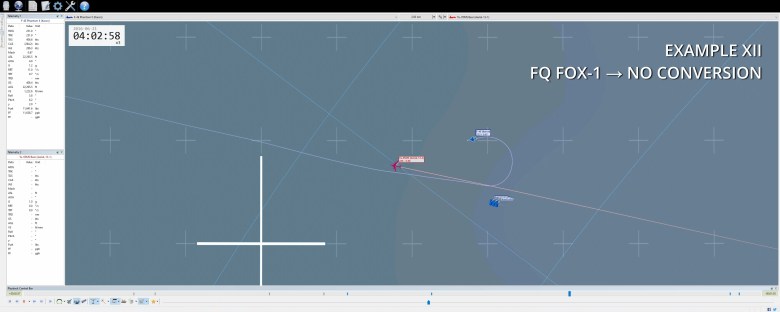

The scenario just explored shows the nature of the problem: without conversion, the fighter would launch its Sparrow and then find itself in an unsuitable position for the follow-up AIM-9. Alternatively, it would end up in a chase after the crank, thus out of the missile WEZ, or Weapon Employment Zone. Both cases are inefficient, as they cost time, fuel, and throw away a potential positional advantage.

In this regard, the sooner a target is defeated, the sooner the fighter can carry on with its tasks. In other words, if the crew has an opportunity to capitalise on a situation, they should take it.

Let’s consider another example to highlight further the importance of the conversion against Pure Pursuit. In this case, I employed the AIM-7 as usual, but then I put the target on the nose, following a pure pursuit path. This may be acceptable for a further Sparrow shot, although Lead Collision or centring the ASE is better kinematics-wise, but it makes the usage of rear-quarter only AIM-9 quite an odd proposition. Moreover, if the targets can fight back and, for example, have a missile already in the air, this manoeuvre does them a favour.

What has been discussed becomes even more relevant when the fighter engages a non-cooperative target or an aware fighter.

These scenarios should have demonstrated how introducing a variation in terms of tactics and geometry can solve an apparently almost insurmountable problem. In this case, the issue was the inefficient transition from an AIM-7 into an AIM-9 shot. The beauty of it, and of the game itself, is that there are untold multitudes of other possibilities and variations.

Before moving to the conclusions, let’s see a final comparison between a stern conversion and pure pursuit.

It should now be clear how the two techniques solve different problems, depending on the many parameters characterising the mission. The critical point is that you know these solutions exist and, with experience and practice, develop the ability to discern which works best and apply it.

Conclusions

A lot has been discussed in this article. So here are some points worth reiterating.

- The “First Launch Opportunity” range of a missile, its kinematics properties, guidance, rocket motor characteristics, et cetera, are all variables that contribute to assessing its capabilities. All should be considered together, not just one.

- Launching at the maximum range just to “force the target to defend” usually does not work unless the target is an ab initio player or the ineffective default AI of DCS. On the other hand, it can be a legit part of a more thought game plan.

- Timelines are organisational tools that help to structure engagement. Like other similar constructs, they have pros and cons that must be addressed, particularly if they are applied outside familiar situations.

- The beauty of this game is the freedom to use tactics and concepts from different eras to gain an advantage. DCS and similar games are also excellent gateways to history, technology, maths and many more topics.

- The safest way to defend against a missile is not to be in a vulnerable position. Avoid relying on flawed mechanics such as notching or chaffs. They create bad habits. Hopefully, one day, they will see improvements and more realism. Chaff, for example, is RNG-based at the moment. For this reason, I did not use it when defending.

I hope you have found this “tip of the iceberg” discussion useful. If you have, please consider following FlyAndWire on YouTube and other media!