This article is intentionally facilitated to help ab initio players, and introduces fundamental topics in a simple and concise way.

Inertial Navigation Systems, or INS for short, are present in most DCS modules. Unfortunately, they are often overlooked, either because they are simply misunderstood or because of their simplistic implementation. This video introduces and discusses the issues, drawbacks and the crew’s role in maintaining an accurate INS.

Although the presence or reliability of an Inertial Navigation System depends on the aircraft used and the specific type and model, we can discuss it using the “ol’ reliable” black box approach. From this perspective, the INS receives speed and attitude-related inputs as the flight progresses and provides positional updates, all without requiring external references besides a known starting point. This type of computation is called “dead reckoning”.

In “Principia Mathematica Philosophiae Naturalis”, 1686, Sir Isaac Newton describes his three laws of motion, from which the following concepts are derived: Inertia, Application of Force, Principle of Action and Reaction.

In particular, Inertia refers to the propriety of an object to remain at rest if already at rest. If in motion, as long as no forces change the status quo, the object will maintain the characteristics of the motion.

The inputs digested by the INS vary, including acceleration and attitude of different axes. Devices such as gyroscopes and accelerometers are used to determine and quantify the forces. After computing, filtering, and elaborating data, the Inertial Navigation System feeds the parameters to navigation, weapon-related computers, crew displays, et cetera.

For these reasons, a faulty INS can interfere with determining the aircraft’s position and with ordnance employment, both air-to-air and air-to-ground.

INS, gyroscopes, and accelerometers are complex devices. Several videos and media about such devices are available on YouTube and other sources. Here are three examples.

- KB-2HM Inertial Platform of a MiG-23 – François Gissy;

- Litton LN-3 Inertial Navigation System of an F-104 Starfighter – François Gissy;

- Startup of a Russian “type 458” gyro block of a MiG-21 fighter after almost 40years of storage – barjan82.

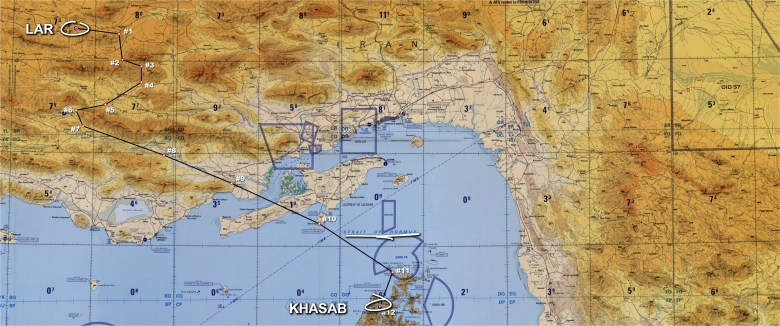

Flightplan Example

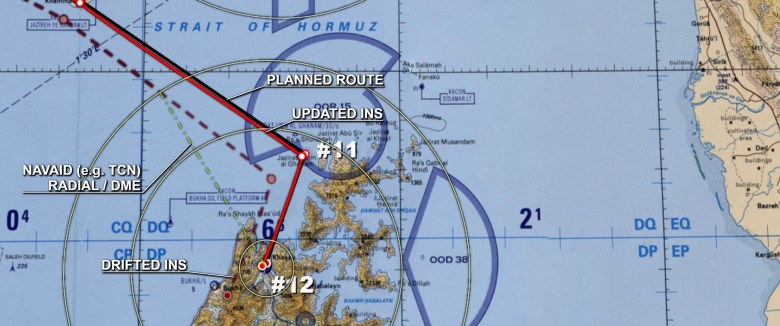

In this example, the flight plan sees our aircraft departing from LAR airport, acronym for Larestan Ayatollah Ayatollahi, and flying a panoramic route over the valleys of the Fars and the Hormozgan provinces. Then, the plan is to turn South-East, cross the Straight of Hormuz, and finally approach Khasab in the Sultanate of Oman for full stop landing. To ease navigation, we can identify a dozen waypoints. So far, it’s all easy, but how does the situation look from the INS’ perspective?

This is, in a simplified image, how an Inertial Navigation System such as the F-4E’s AN/ASN-63 sees the world at startup. The only known position is either stored in the INS’ memory or selected by the Weapon Systems Officer.

At some point before departure, the WSO can add the only available nav point. From this moment forward, the INS will see the outside world as a blindfolded passenger in a car would do. Reassuring, eh?

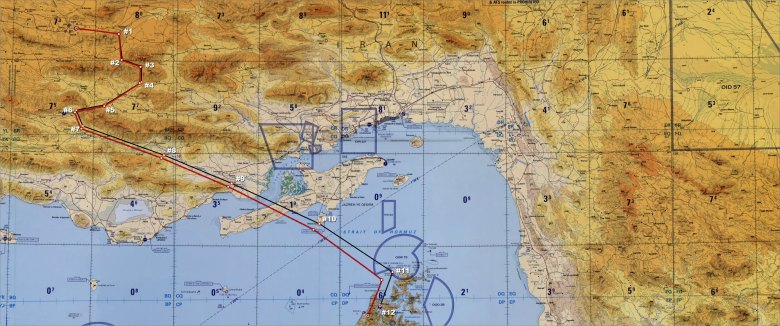

After the steerpoint is reached, the new next waypoint is inserted and the flight continues. This technique is called “leapfrogging”. If you are unfamiliar with it, check this article.

Each leg may have a different cruising altitude due to the uneven terrain or speed. Eventually, the aircraft reaches its destination, slows down and prepares for landing.

When the lights are switched on again, so to speak, we immediately see that something is off: the theoretical destination and the actual one differ by a few miles. How come? Let’s find out!

INS issues

Every Inertial Navigation System suffers from a systematic and intrinsic error-accumulation phenomenon. In the mentioned AN/ASN-63, the INS accumulates 3 nm CEP, or Circular Error Probability, when the best alignment is used. Otherwise, the error doubles. Simplifying, half of the time, the error should fall within ±1.5 nm from the theoretical destination in the best-case scenario.

In addition, turns and attitude changes, especially hard manoeuvres, can negatively affect the Inertial Navigation System. In the worst-case scenario, the INS can be “bent” and become inoperable, and, in extreme cases, the aircraft itself can suffer catastrophic damage.

Although most aircraft in DCS feature an INS, its implementation is often highly simplified. Modules made by the Heatblur team are instead incredibly well and accurately recreated. The images available here (ED forum) show the difference in the flight path of a Tomcat and what its AN ASN-92 cains sees. Another example of Heatblur’s excellent work and attention to detail is the AHRS gyroscopes re-erection to compensate for the error induced by Carrier operations. This fundamental post-departure operation is mentioned in several sources, interviews and books, such as Dave “Bio” Baranek’s “Tomcat RIO”. Every F-14 player should also be very familiar with it. If you are not, check the links below:

- AN/ASN-92 INS Part III: Carrier Operations;

- AN/ASN-92 AHRS Gyros Re-erection. When I wrote the article above, a bug prevented the AHRS to be sorted in specific situations. This article explains how the gyros can properly addressed.

- AN/ANS-92 Fix Updates & Troubleshooting. This article contains the extract from a chat with Dave “Bio” Baranek (ex F-14 RIO) who I contacted in order to understand and help addressing the AHRS issued mentioned above. On top of that, a chat with another ex F-14A RIO, Scott “Weird” Altorfer, sharing his view about some of the issues affecting the AN/ASN-92.

Help the INS to help you

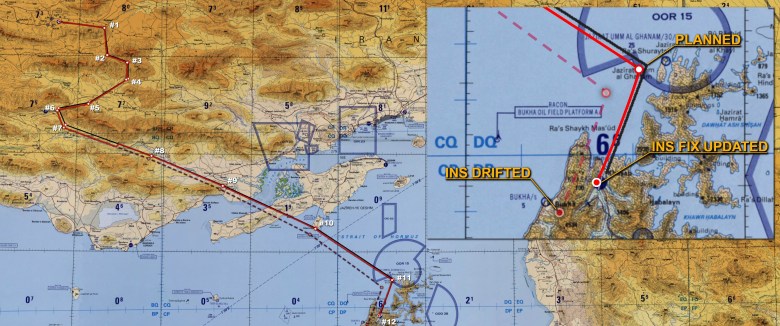

Back to the scenario, the situation is not as dire as it may seem at first glance. Since the INS works by updating a known point, the crew can update the so-called Fix, thus reducing the positional discrepancy for the time being.

Such an update can be performed in many ways, such as correlating the discrepancy from a known position (e.g., a TACAN station) to a radar or visual fix. DCS, being a game, even allows players to come up with funny ways of sorting out this problem. My favourite in the Tomcat is copying the coordinates from the GPS if the mission era setting is coherent with its usage. This method also works for the F-4E Phantom II.

As mentioned, the primary effect of updating the INS Fix is changing where the aircraft “thinks” it is, so to speak. However, the drift is still present and will accumulate over time, and a possible further update may be required later on. Moreover, this operation will not correct any issue caused by battle damage or harsh manoeuvres.

The following are a series of methods to update the INS Fix (AN/ANS-92 only at the moment, AN/ASN-63 soon ™):

Augmenting Navigation

The list of issues described makes the Inertial Navigation System a great tool to have, but insufficient on its own, at least until laser-gyros and GNSS augmentation were introduced. Although the former are vastly more accurate than analogue INS devices, they still raise, on average and for standard components, an error of circa 1 nm per hour of flight. This on top of the intrinsic greater reliability of digital components. The GPS augmentation instead allows the INS to correct its estimated position via satellite using different techniques and providing a de facto drift-free position. Unless, of course, someone decides to jam or spoof the signal or have fun with the satellites.

On the bright side, no matter the technology used, there are techniques to make flight plans more reliable and less prone to the INS’s fits. For instance, pilotage, dead-reckoning, NAVAIDs, and more.

In particular, and in the era when the F-4E-45MC was in active service, NAVAIDs, maps, pilotage, and so on, were all techniques used to supplement or replace INS navigation. Back to our example, most airfields and other locations may have some sort of NAVAID. Therefore, the crew can use the INS to roughly follow the flight plan, then monitor or correct following TACAN or even VOR bearing and range, if a DME is present. Pilotage can also be used to identify the promontoire north of the Omani peninsula. Then, the crew can intercept the Khasab TACAN and fly radial and DME until the aircraft position is correct and landing preparations are initiated. Again, this is a heavily simplified example. Weather, mission, task, and payload are just some of the parameters the crew must take into account whilst planning the flight plan.

Conclusions

A way of better understanding Inertial Navigation Systems is by seeing them as any other tool available to the crew. For instance, radars have to deal with ground clutter, beaming targets, lack of Doppler, target’s Radar Cross Section, and much more. The ordnance we employ has similar yet different issues. No one ever considers an air-to-air missile as a done deal with 100% PK. In a parallel manner, INS navigation has to deal with a number of issues and limitations, the drift in primis. Once these phenomena are understood and considered part of aircraft management, they become part of planning and flight routine. The sooner players, and new players especially, understand this, the earlier they will acquire the ability to make the best out of their aircraft.

Description: “English: Ring laser gyroscope produced by Ukrainian “Arsenal” factory on display at MAKS-2011 airshow

Русский: Кольцевой лазерный гироскоп производства украинского завода “Арсенал” в одном из павильонов авиасалона МАКС-2011″

Author: Nockson

Link: Wikipedia